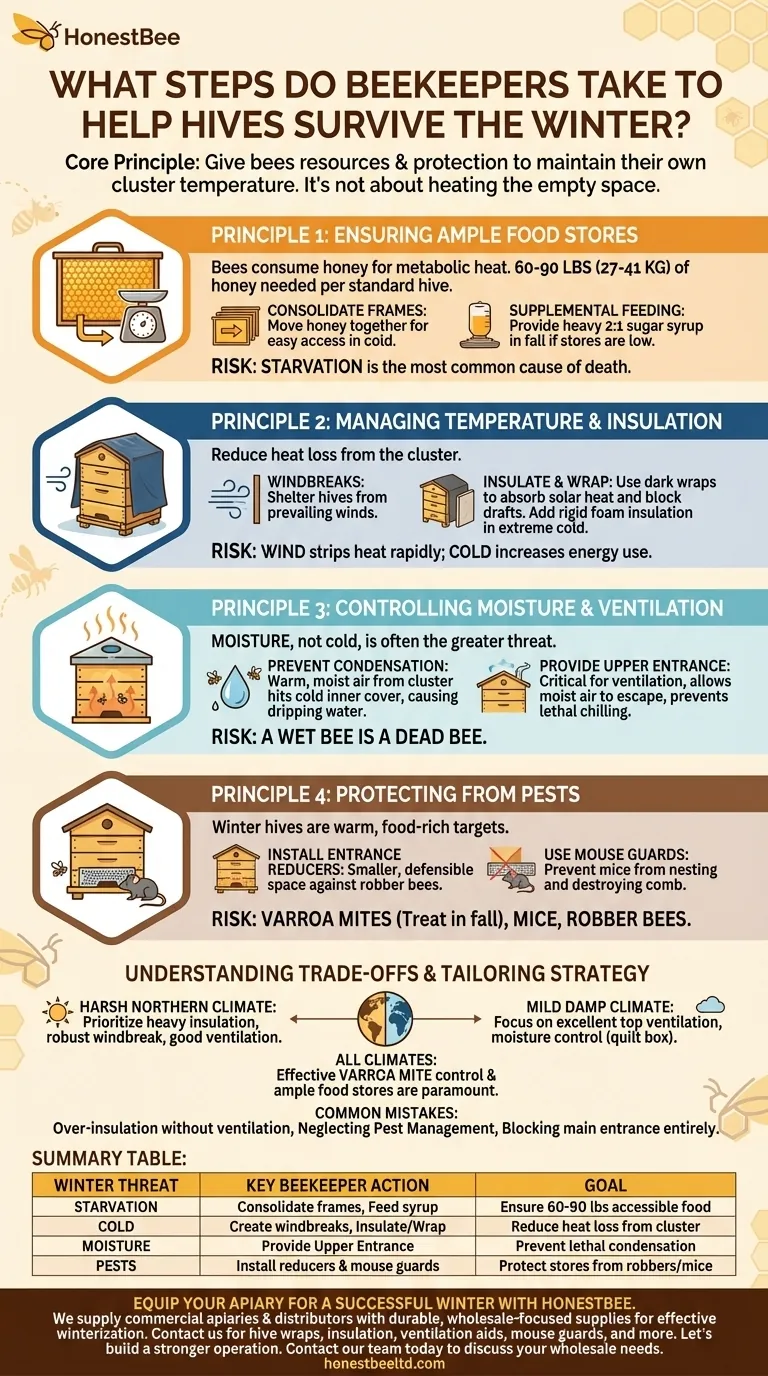

To ensure a honeybee colony survives the winter, a beekeeper must manage four critical threats: starvation, cold, moisture, and pests. This involves a series of proactive steps in the autumn, from consolidating food stores and insulating the hive to controlling pests and ensuring proper ventilation. Success is not about keeping the hive interior warm, but about giving the bees the resources and protection they need to keep themselves warm.

The core principle of winterizing a hive is not to heat the empty space, but to help the bees maintain the temperature of their own tight cluster. Your goal is to provide a dry, draft-free, and well-stocked pantry that is safe from intruders.

Principle 1: Ensuring Ample Food Stores

A colony's primary winter activity is consuming stored honey to generate heat. Running out of food is the most common cause of winter death.

The Risk of Starvation

Honeybees do not hibernate. Instead, they form a tight "winter cluster" and vibrate their wing muscles to generate heat, maintaining a core temperature of around 95°F (35°C). This metabolic activity requires a massive amount of energy, which comes directly from their honey stores.

A standard, full-depth hive may need 60-90 pounds (27-41 kg) of honey to survive a cold winter.

Consolidating Honey Frames

Bees in a cold cluster are often unwilling or unable to move across empty frames to reach food on the other side of the hive. They can starve just inches away from honey.

Beekeepers prevent this by moving all the frames of honey together in the fall, typically in the upper hive box. This creates a contiguous, uninterrupted pantry directly above where the winter cluster will form.

Supplemental Feeding

If a colony's natural stores are insufficient after the final honey harvest, beekeepers provide supplemental feed. This is usually a heavy sugar syrup (a 2:1 ratio of sugar to water) given in the fall.

This feeding must be done early enough that the bees have time to process the syrup, store it in the comb, and dehydrate it before cold weather sets in.

Principle 2: Managing Temperature and Insulation

The goal of insulation is to reduce the rate of heat loss from the hive, allowing the bees to consume less honey to stay warm.

The Importance of Windbreaks

Wind is more dangerous than still, cold air because it rapidly strips heat from the hive's outer surfaces. A primary step is to either place the hive in a location naturally sheltered from prevailing winter winds or to create a windbreak.

Insulating and Wrapping Hives

Many beekeepers wrap their hives, often with black tar paper or specialized hive wraps. The black color helps absorb solar energy on sunny days, while the wrap itself serves as an insulating layer that blocks wind.

The choice of insulation material should be based on your specific climate. In extremely cold regions, rigid foam insulation boards placed inside or outside the hive body are common.

Principle 3: Controlling Moisture and Ventilation

Moisture, not cold, is often the more immediate threat to a wintering colony.

The Danger of Condensation

A cluster of bees breathing and metabolizing honey releases a significant amount of warm, moist air. When this air rises and hits the cold inner cover of the hive, it condenses into water.

If this water drips back down onto the bees, it can quickly chill and kill them. A wet bee is a dead bee.

Providing an Upper Entrance

Proper ventilation is the solution to condensation. While it seems counterintuitive to create an opening in a hive you're trying to keep warm, it is absolutely critical.

An upper entrance, often a small hole drilled in the top hive box or included in the hive wrap, allows the warm, moist air to escape. This prevents condensation from forming and dripping on the cluster.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Pitfalls

Winterizing is a balancing act. Misunderstanding the core principles can do more harm than good.

Over-Insulation and Poor Ventilation

The most common mistake is insulating a hive without providing adequate ventilation. Sealing a hive up "tight" to keep it warm will trap moisture, creating a cold, damp environment that is far more lethal than a dry, drafty one.

Neglecting Pest Management

A colony weakened by a high Varroa mite load has a very poor chance of surviving winter. These parasitic mites feed on bees, transmit viruses, and shorten their lifespan. Aggressive mite testing and treatment in the late summer and fall are non-negotiable.

Blocking the Main Entrance Entirely

While reducing the entrance size is crucial, blocking it completely prevents bees from taking "cleansing flights" on warmer winter days to defecate. An obstructed entrance can lead to dysentery and disease within the hive.

Principle 4: Protecting the Hive from Pests

A wintering hive is a warm, food-rich target for intruders.

Installing Entrance Reducers

In the fall, the large summer entrance is reduced to a small opening. This gives the diminished colony a smaller, more defensible space to guard against robbing bees from other hives who are seeking to steal their honey stores.

Using Mouse Guards

Mice seeking warmth and food will readily move into a hive for the winter. Once inside, they will destroy comb, eat honey and bees, and create a mess that can lead to the colony's demise.

A mouse guard, which is a metal or plastic strip with holes large enough for bees but too small for mice, is installed over the reduced entrance.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your winterization strategy should be tailored to your specific climate and conditions.

- If your primary focus is surviving a harsh, northern climate: Heavy insulation, a robust windbreak, and a well-designed ventilation system to handle extreme temperature differences are your top priorities.

- If your primary focus is navigating a milder, damp climate: Your main concern is moisture control. Ensure excellent top ventilation and consider using a quilt box to absorb condensation.

- For all beekeepers, regardless of location: The health of your colony is paramount. Prioritize effective Varroa mite control and ensure the hive has more than enough food to last until spring.

Ultimately, successful wintering empowers a strong, healthy colony to do what it does best: survive.

Summary Table:

| Winter Threat | Key Beekeeper Action | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Starvation | Consolidate honey frames; Provide supplemental feeding | Ensure 60-90 lbs of accessible food stores |

| Cold | Create windbreaks; Insulate/wrap the hive | Reduce heat loss from the bee cluster |

| Moisture | Provide an upper entrance for ventilation | Prevent lethal condensation from dripping on bees |

| Pests | Install entrance reducers and mouse guards | Protect honey stores from robbers and mice |

Equip Your Apiary for a Successful Winter with HONESTBEE

Ensure your colonies have the best chance of survival. HONESTBEE supplies commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors with the durable, wholesale-focused supplies needed for effective winterization—from hive wraps and insulation to ventilation aids and mouse guards.

Let us help you build a stronger, more resilient operation.

Contact our team today to discuss your wholesale needs and get your hives ready for the cold.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Professional Bamboo Queen Isolation Cage

- Professional Galvanized Hive Strap with Secure Locking Buckle for Beekeeping

- Black Plastic Beetle Barn Hive Beetle Trap for Beehives

- Professional Grade Foldable Beehive Handles

- Langstroth Screen Bottom Board for Beekeeping Wholesale

People Also Ask

- Why use specialized Queen Introduction Cages? Protect Your Investment and Ensure Successful Hive Succession

- What is the key function of a frame-type queen excluder in Varroa treatment? Master Biological Mite Containment

- What role do integrated Varroa calendars play? Optimize Bee Health with Strategic Mite Treatment Guidelines

- What is sequestration, and how does it help bees reorient? A Safer Guide to Hive Relocation

- When is a newly introduced queen considered accepted by the colony? The Definitive Sign You Need to See