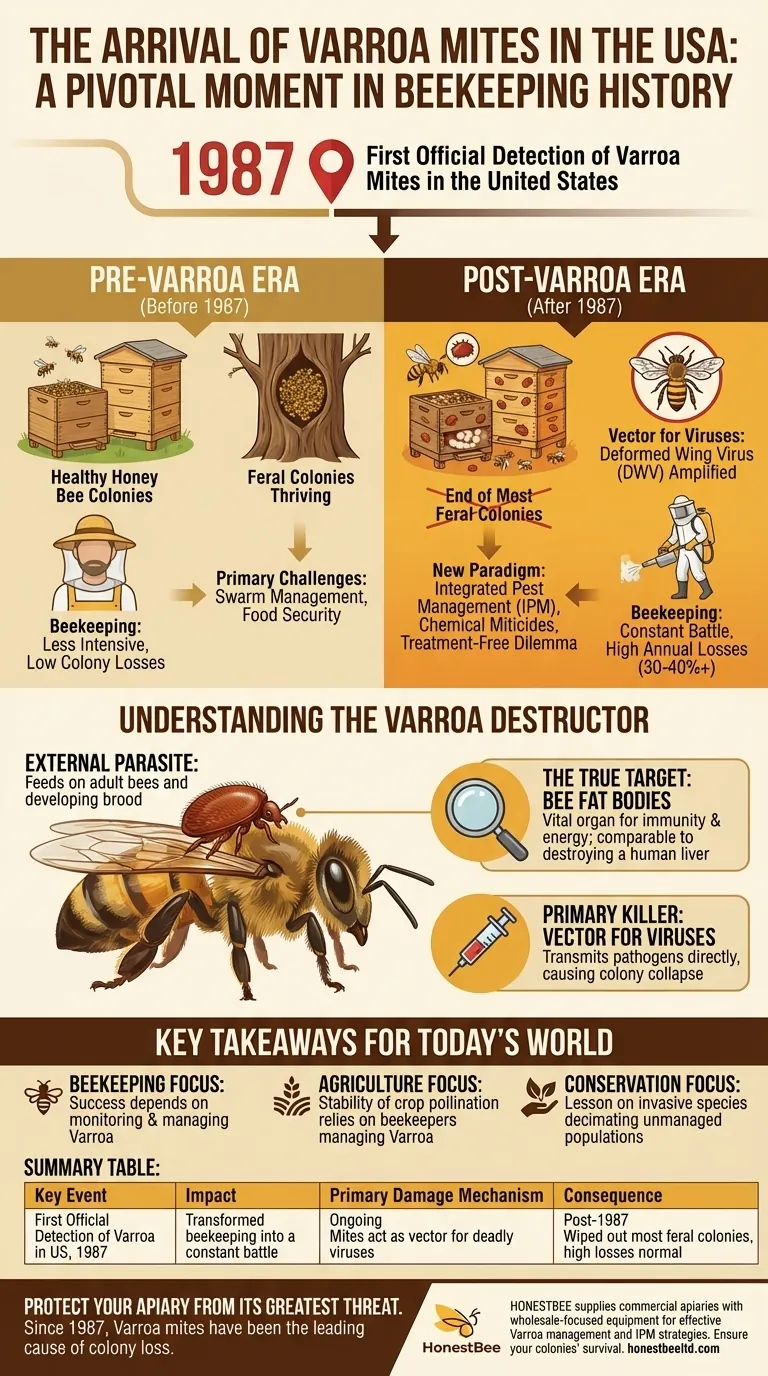

The arrival of the Varroa mite was the single most destructive event in the history of modern American beekeeping. Infested honey bee colonies were first officially detected in the United States in 1987, an event that permanently altered the practice of beekeeping and triggered a cascade of challenges that persist to this day.

The 1987 detection of Varroa destructor was not merely the introduction of a new pest. It marked the end of an era, transforming beekeeping from a relatively straightforward practice into a constant battle for colony survival against a parasite that is now endemic nationwide.

What is the Varroa Destructor?

An External Parasite

The Varroa destructor is a tiny external mite that reproduces within a honey bee colony. It latches onto both adult bees and developing brood (larvae and pupae), feeding on their internal tissues to survive.

The True Target: Bee Fat Bodies

For decades, it was believed that Varroa mites fed on hemolymph, the bee equivalent of blood. We now know they primarily consume the bee's fat body, a vital organ responsible for immune function, detoxification, and energy storage. This is like a parasite destroying a human's liver.

The Primary Killer: A Vector for Viruses

The most devastating impact of the Varroa mite is its role as a vector for deadly viruses. As it feeds, it transmits pathogens directly into the bee's system.

The most prominent of these is the Deformed Wing Virus (DWV). In a colony with low mite levels, DWV may be present but harmless. In a colony with a high Varroa population, the virus is amplified and activated, leading to bees with shrunken, useless wings, paralysis, and a dramatically shortened lifespan. It is this mite-virus combination that causes colony collapse.

The Post-1987 Reality

Rapid Nationwide Spread

After its initial discovery in Wisconsin, the mite spread across the country with incredible speed. This was largely facilitated by the commercial beekeeping industry, which transports tens of thousands of hives across state lines for agricultural pollination services.

The End of Feral Colonies

Prior to 1987, the United States had a robust population of feral or "wild" honey bee colonies living in tree hollows and other natural cavities. These colonies, which received no human intervention, had no defense against the Varroa mite. Within a few years, this unmanaged population was almost entirely wiped out.

A Fundamental Shift in Beekeeping

The arrival of Varroa forced a new paradigm. Beekeeping was no longer about simply providing a box and harvesting honey. It became an exercise in Integrated Pest Management (IPM), where monitoring mite levels and applying treatments became essential for survival.

Understanding the Trade-offs: Beekeeping Before and After Varroa

The Pre-Varroa Era

Before 1987, beekeeping was significantly less intensive. The primary challenges were managing swarm tendencies and ensuring colonies had enough food. Colony losses over winter were far lower, and the idea of a colony simply dying out from "sickness" was uncommon.

The Post-Varroa Era

After 1987, beekeeping became a constant struggle against an unseen enemy. Annual colony losses of 30-40% or more became the new, alarming normal. Beekeepers were forced to become amateur veterinarians, learning to use various chemical miticides to keep their hives alive.

The "Treatment-Free" Dilemma

This new reliance on chemicals created a desire for "treatment-free" beekeeping. While a noble goal, it is exceptionally difficult to achieve. Without some form of active management—either through chemical intervention or the use of specific, mite-resistant bee genetics—a colony with a growing Varroa population is almost certain to perish within one to three years.

Key Takeaways for Today's World

Understanding the 1987 arrival of Varroa is critical to contextualizing the challenges facing honey bees, beekeepers, and our food system.

- If your primary focus is beekeeping: Your success is almost entirely dependent on your ability to monitor and manage Varroa mite populations; it is the central threat to your colonies.

- If your primary focus is agriculture: The stability of crop pollination now relies on beekeepers successfully managing Varroa, adding cost, labor, and risk to the food supply chain.

- If your primary focus is conservation: The Varroa mite serves as a stark lesson in how a single invasive species can decimate unmanaged animal populations and permanently alter an ecosystem.

Recognizing the Varroa mite as the primary driver of honey bee mortality since its 1987 arrival is the essential first step toward responsible stewardship.

Summary Table:

| Key Event | Year | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| First Official Detection of Varroa Mites in the US | 1987 | Transformed beekeeping into a constant battle for survival. |

| Primary Damage Mechanism | Ongoing | Mites act as a vector for deadly viruses like Deformed Wing Virus (DWV). |

| Consequence | Post-1987 | Wiped out most feral colonies; annual colony losses of 30-40% became normal. |

Protect your apiary from its greatest threat. Since 1987, Varroa mites have been the leading cause of colony loss. HONESTBEE supplies commercial apiaries and distributors with the wholesale-focused equipment and supplies needed for effective Varroa management and Integrated Pest Management (IPM) strategies. Ensure your colonies' survival—contact our experts today to discuss your needs.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Professional Bamboo Queen Isolation Cage

- Metal Queen Bee Excluder for Beekeeping

- Premium Wood Framed Metal Wire Queen Bee Excluder

- High Performance Plastic Queen Excluder for Beekeeping and Apiary Management

- Professional Plastic Queen Excluder for Modern Beekeeping

People Also Ask

- Why use specialized Queen Introduction Cages? Protect Your Investment and Ensure Successful Hive Succession

- What is the argument for removing attendant bees from a queen cage? Ensure Safe Queen Bee Introduction

- What is the key function of a frame-type queen excluder in Varroa treatment? Master Biological Mite Containment

- How does the use of queen cages contribute to the effectiveness of honeybee treatments? Optimize Varroa Mite Eradication

- What is the purpose of using plastic containers with ventilation holes? Ensure Bee Health and Sample Data Integrity