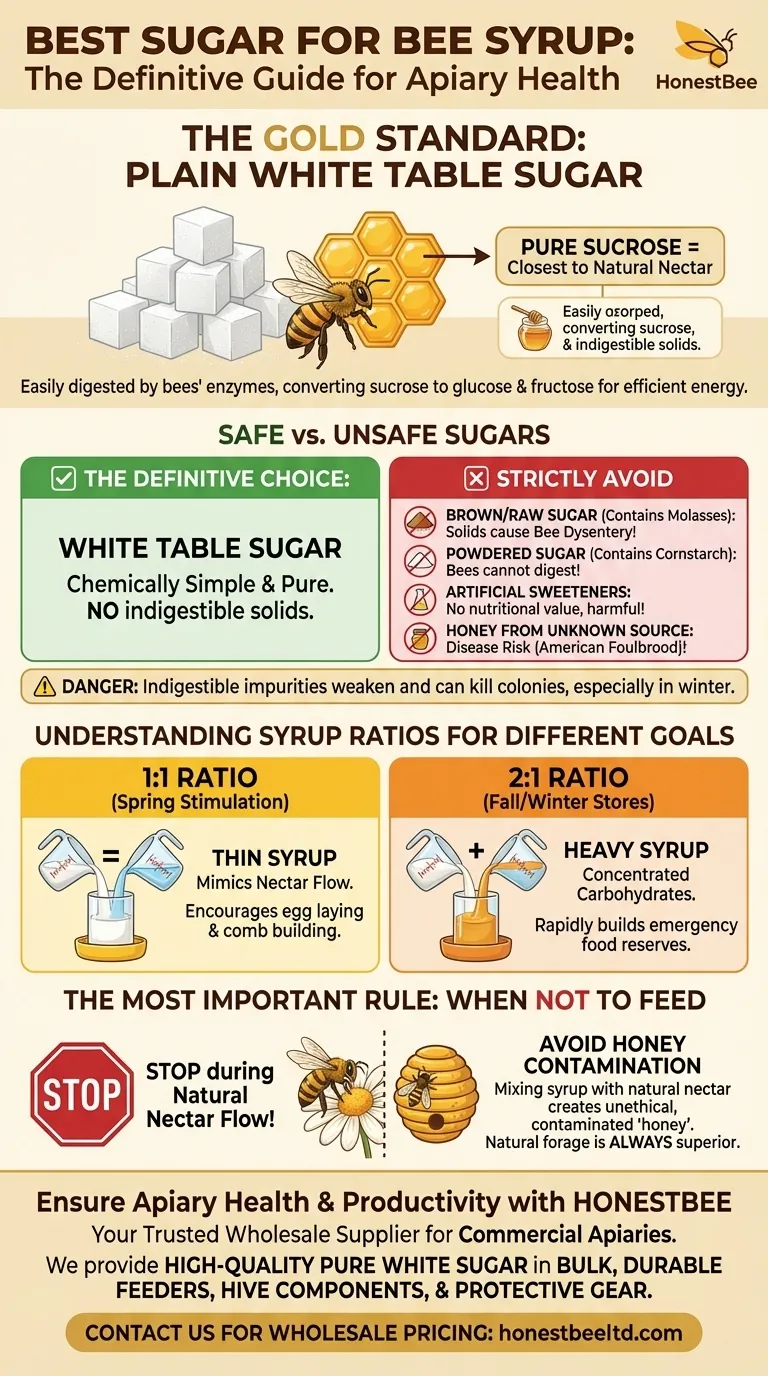

The definitive and safest choice for making bee syrup is plain white table sugar. This pure sucrose is the closest artificial food source to natural nectar, allowing bees to process it easily without the risk of digestive harm. Any other type of sugar introduces unnecessary compounds that can be detrimental to the health of your colony.

The core principle of feeding bees is to supplement their diet with a substance that is as chemically simple and pure as natural nectar. Plain white sugar (sucrose) is the only option that meets this standard, while other sweeteners introduce dangerous impurities bees cannot digest.

Why Plain White Sugar is the Gold Standard

Mimicking Natural Nectar

Honey bee nutrition is optimized for processing simple sugars. The primary sugar found in floral nectar is sucrose, which is the exact chemical composition of refined white sugar.

Bees produce an enzyme called invertase, which breaks down sucrose into the simpler sugars glucose and fructose. This makes pure white sugar an easily digestible and efficient energy source for them.

The Dangers of Solids and Impurities

The critical reason to avoid other sugars is that they contain compounds bees cannot digest. Brown, raw, or turbinado sugars get their color and flavor from molasses, which contains solids and minerals.

Since bees are unable to process these solids, they can accumulate in their digestive tracts. This often leads to a severe condition known as bee dysentery, which can weaken and even kill a colony, especially during winter confinement.

Sugars and Sweeteners to Strictly Avoid

To protect your bees, never use the following to make syrup:

- Brown or Raw Sugar: Contains indigestible molasses.

- Powdered Sugar: Almost always contains anti-caking agents like cornstarch, which bees cannot digest.

- Artificial Sweeteners: Offer no nutritional value and can be harmful.

- Honey from an Unknown Source: Can carry devastating diseases like American Foulbrood spores, which can infect your entire colony.

Understanding Syrup Ratios for Different Goals

The ratio of sugar to water you use depends entirely on what you are trying to accomplish for the colony. The two standard ratios serve very different purposes.

The 1:1 Ratio: Simulating a Nectar Flow

A 1:1 ratio of sugar to water by weight creates a thin syrup. This mixture closely mimics the consistency of a natural spring nectar flow.

Feeding 1:1 syrup is primarily used to stimulate the colony. It encourages the queen to lay more eggs and prompts the bees to begin drawing out new wax comb on foundation.

The 2:1 Ratio: Building Winter Stores

A 2:1 ratio of sugar to water by weight creates a heavy, dense syrup. This mixture is less about stimulation and more about providing a concentrated source of carbohydrates.

This heavy syrup is used when honey stores are low, typically in the fall. The goal is to help the bees quickly build up the food reserves they need to survive the winter.

The Most Important Rule: When Not to Feed

While supplemental feeding is a critical tool, it's essential to know when to stop. You should never feed sugar syrup to a colony when a natural nectar flow is available.

Avoiding Honey Contamination

If you feed during a nectar flow, the bees will collect and store the sugar syrup right alongside the natural nectar. This results in "honey" that is contaminated with sugar syrup, which is unethical to harvest and sell.

Natural Forage is Always Superior

A colony with access to sufficient natural nectar and pollen is always healthier. Feeding is a targeted intervention for specific situations, such as colony establishment, dearth, or fall preparation. It is not a replacement for natural forage.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

- If your primary focus is stimulating spring growth and comb building: Use a 1:1 syrup ratio made exclusively with pure white sugar.

- If your primary focus is building emergency food stores for winter: Use a 2:1 syrup ratio to provide a dense, high-calorie food source.

- If your primary focus is harvesting pure, natural honey: Cease all feeding as soon as a natural nectar flow begins in your area.

By using the right type of sugar at the right time, you can provide powerful support that ensures a healthy and productive colony.

Summary Table:

| Sugar Type | Safe for Bees? | Key Reason |

|---|---|---|

| White Table Sugar (Sucrose) | Yes | Pure sucrose, mimics natural nectar, easily digested |

| Brown/Raw Sugar | No | Contains indigestible molasses solids |

| Powdered Sugar | No | Contains anti-caking agents like cornstarch |

| Honey (Unknown Source) | No | Risk of spreading diseases like American Foulbrood |

| Artificial Sweeteners | No | No nutritional value, potentially harmful |

Ensure your apiary's health and productivity with the right supplies from HONESTBEE.

Feeding your bees correctly is just one part of successful beekeeping. As a trusted wholesale supplier for commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors, HONESTBEE provides the high-quality, reliable supplies you need to manage thriving colonies at scale.

We offer everything from pure white sugar in bulk for syrup making to durable feeders, hive components, and protective gear designed for professional use.

Let's discuss your specific needs. Contact our expert team today to get wholesale pricing on the equipment and consumables that support healthy, productive bees season after season.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- HONESTBEE Professional Entrance Bee Feeder Hive Nutrition Solution

- Wholesales Dadant Size Wooden Bee Hives for Beekeeping

- Yellow Plastic Bucket Pail Perch for Beekeeping

- Extra Wide Stainless Steel Honey Uncapping Fork with Scraper Beekeeping Tool

- Long Langstroth Style Horizontal Top Bar Hive for Wholesale

People Also Ask

- What are the advantages of commercial protein enhancers for bees? Boost Colony Health with Advanced Nutrition

- How do high-quality syrups and protein supplements facilitate early-season commercial pollination contracts?

- What are the placement and advantages of bucket feeders? Master High-Volume Hive Feeding

- What are the significant drawbacks of the dry pollen feeding method? Manage Risks and Biosecurity in Your Apiary

- How do bees enter a bee rapid feeder? Discover the Safe Internal Access Design

- What is the recommended distance between a beehive and its water source? Boost Your Hive's Efficiency

- What are top feeders, and where are they placed? A Guide to High-Capacity Hive Feeding

- How were sham sugar patties prepared for the Control group? A Guide to Creating a Valid Placebo