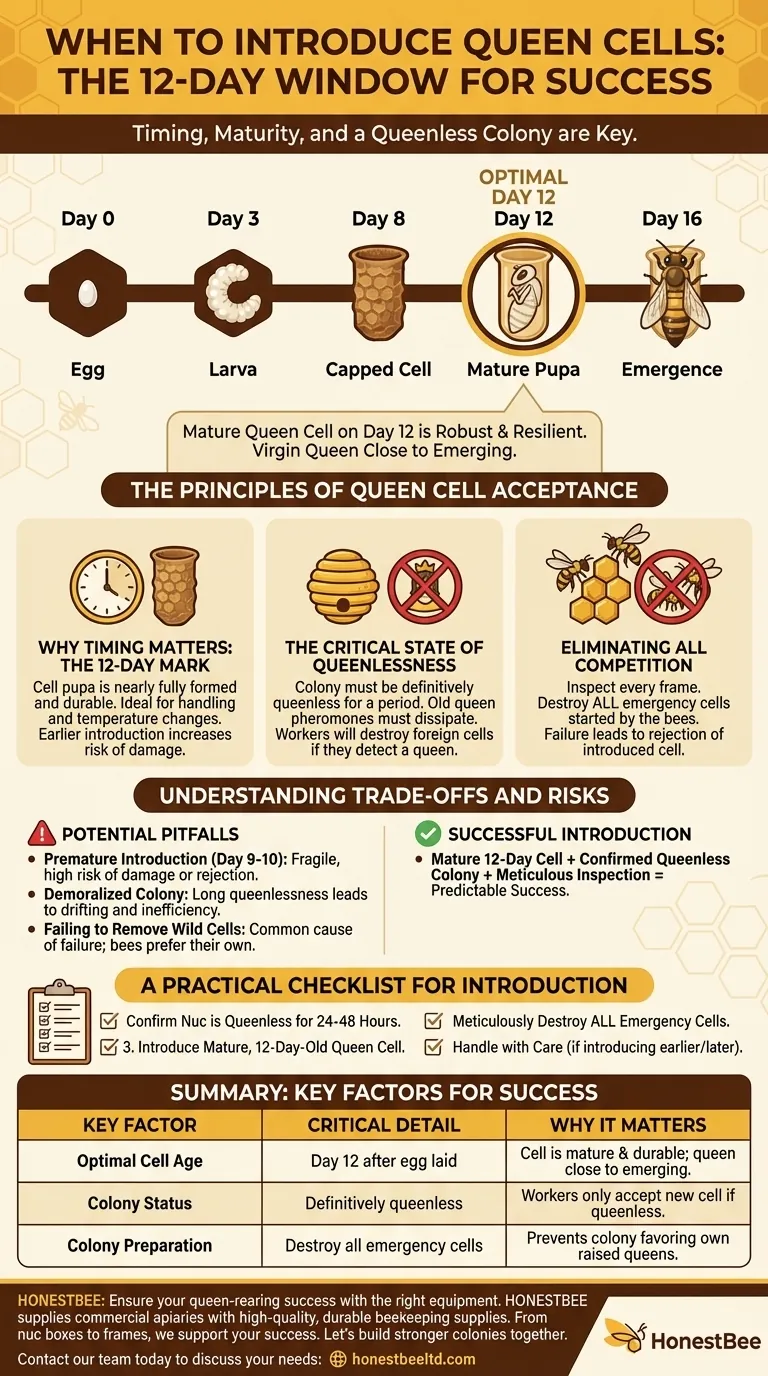

The critical window for introducing a queen cell is determined by the cell's maturity and the recipient colony's state of mind. You can safely give a mature queen cell to a nucleus colony (a "nuc") on day 12 after the egg was first laid. This timing ensures the cell is robust enough for handling and the virgin queen is close to emerging, minimizing the period the colony remains queenless.

Success depends less on the exact hour of introduction and more on ensuring the recipient nucleus colony is hopelessly queenless, with no other option but to accept the cell you provide.

The Principles of Queen Cell Acceptance

A colony's decision to accept or destroy a new queen cell is not random; it is governed by a strict set of biological triggers. Understanding these principles is the key to a successful introduction.

Why Timing Matters: The 12-Day Mark

On day 12 of a queen's 16-day development cycle, the pupa inside the cell is nearly fully formed. The cell has been capped for several days and is at its most durable.

Introducing a cell at this stage is ideal because it is resilient to slight temperature changes and the handling required to place it in the nuc. While introduction may be possible earlier, it comes with a higher risk of chilling or damaging the delicate pupa.

The Critical State of Queenlessness

A honey bee colony will only accept a new queen—or queen cell—if it knows it does not have one. The presence of a queen's pheromones will trigger the worker bees to immediately destroy any foreign queen cells.

Therefore, the nucleus colony must be definitively queenless for a period before introduction. This allows the old queen's scent to dissipate and for the colony to recognize its urgent need for a replacement.

Eliminating All Competition

A queenless colony's first instinct is to create its own new queens from any existing eggs or young larvae. These are known as emergency cells.

Before you insert your raised cell, it is essential to inspect every frame in the nucleus and destroy all emergency cells the bees have started to build. If you fail to do this, the bees will likely favor the queens they have started to raise themselves and destroy the cell you have provided.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Risks

While the process is straightforward, missteps can lead to failure. Awareness of the potential pitfalls is crucial for consistent success.

The Risk of Premature Introduction

Introducing a cell that is too young (e.g., 9-10 days old) makes it highly vulnerable. The pupa is more fragile, and the bees may perceive the immature cell as defective and tear it down.

The Danger of a Demoralized Colony

A colony left queenless for too long can become demoralized. The reference to bees becoming "discontented" points to this phenomenon.

Workers may stop foraging efficiently, and some may begin drifting to other, stronger queenright hives in the apiary. This weakens the nuc and reduces its chances of building up into a productive colony once the new queen emerges and mates.

Failing to Remove Wild Cells

The single most common reason for failure is leaving one or more emergency cells in the nucleus. The bees will almost always prefer a queen they have raised from their own brood, even if your introduced cell is from genetically superior stock.

A Practical Checklist for Introduction

Your specific approach should align with your primary goal and experience level.

- If your primary focus is maximizing the success rate: Introduce a mature, 12-day-old cell into a nuc that has been confirmed queenless for 24-48 hours, after meticulously destroying all emergency cells.

- If you are an experienced beekeeper needing to act quickly: You can introduce cells slightly earlier (10-11 days), but you must handle them with extreme care to avoid chilling or jarring the delicate pupa inside.

- If you discover emergency cells in your nuc: Always destroy them without exception, as a colony with other options will almost certainly reject your introduced cell.

Proper timing combined with thorough preparation transforms a risky introduction into a predictable success.

Summary Table:

| Key Factor | Critical Detail | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Cell Age | Day 12 after the egg was laid | Cell is mature and durable for handling; queen is close to emerging. |

| Colony Status | Must be definitively queenless | Worker bees will only accept a new cell if they know they are queenless. |

| Colony Preparation | Destroy all emergency queen cells | Prevents the colony from favoring its own raised queens over your introduced cell. |

Ensure your queen-rearing success with the right equipment.

A successful introduction starts with a strong, healthy nucleus colony. HONESTBEE supplies commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors with the high-quality, durable supplies needed to build and manage productive nucs. From nuc boxes and frames to protective gear, our wholesale-focused operations ensure you get the reliable equipment your operation depends on.

Let's build stronger colonies together. Contact our team today to discuss your beekeeping supply needs and how we can support your success.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 5 Frame Wooden Nuc Box for Beekeeping

- Twin Queen Styrofoam Honey Bee Nucs Mating and Breeding Box

- Automatic Heat Preservation 6 Frame Pro Nuc Box for Honey Bee Queen Mating

- Styrofoam Mini Mating Nuc Box with Frames Feeder Styrofoam Bee Hives 3 Frame Nuc Box

- Portable Bee Mating Hive Boxes Mini Mating Nucs 8 Frames for Queen Rearing

People Also Ask

- What is a baby nuc, also known as a mating nuc? Boost Queen Rearing Efficiency Today

- What are the advantages of using mating nucleus hives? Optimize Genetic Selection & Scale Your Queen Rearing Efficiently

- What are the primary uses of Nucleus colonies in beekeeping? Essential Tools for Apiary Growth and Queen Rearing

- What frames should be removed from a queenless, full-size colony when requeening with a nuc? A Strategic Guide for Success

- What precautions should be taken to protect the queen when transferring frames from a nuc? Ensure Safe Hive Transfers

- What are the differences between a Mating Nuc and a Standard Nucleus Hive? Master High-Efficiency Queen Rearing

- How should a parent colony be prepared before it is split to create a nuc? Optimize Hive Growth for Success

- What essential equipment and supplies are required before installing a nucleus colony (nuc)? Ultimate Apiary Checklist