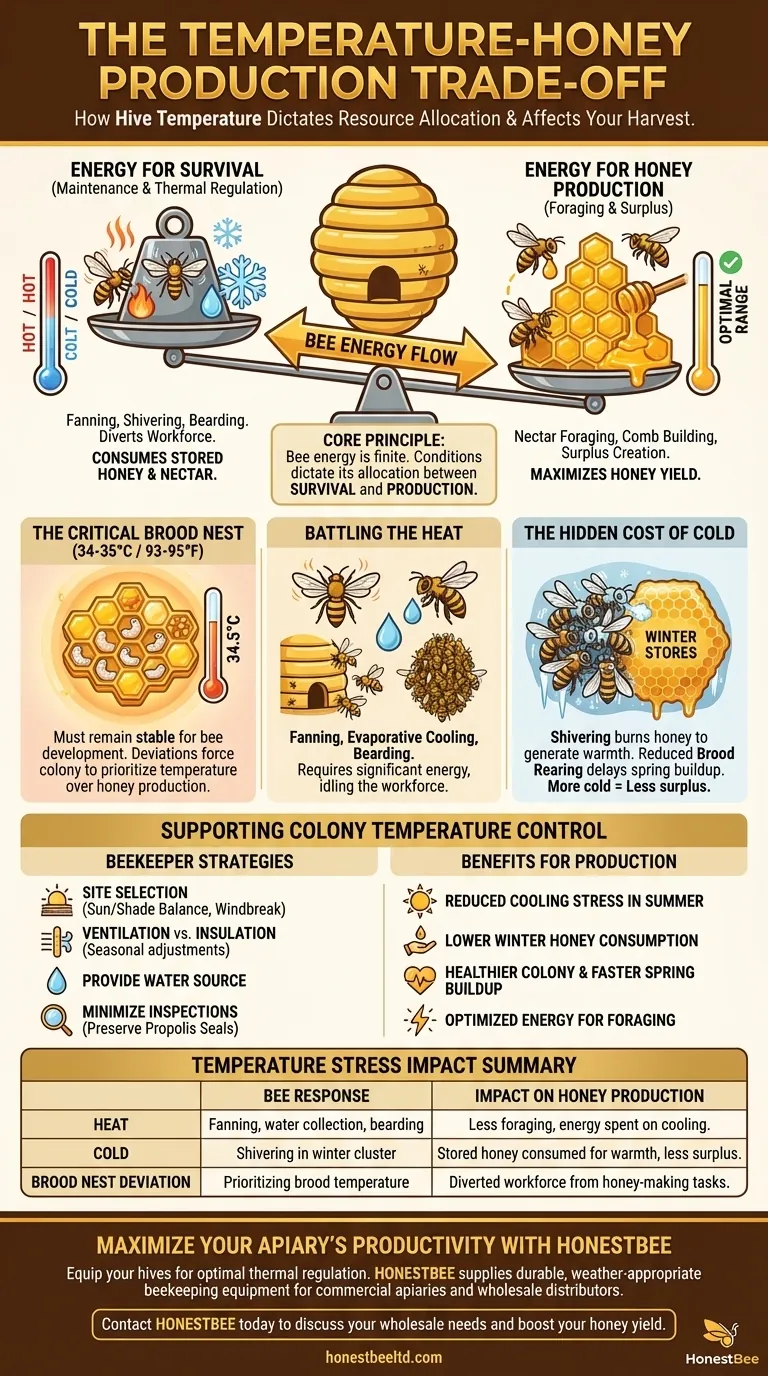

Ultimately, hive temperature dictates resource allocation. A bee colony is a superorganism that must maintain a stable internal environment, and any energy spent fighting temperature extremes is energy diverted from foraging for nectar and producing honey. If the hive becomes too hot or too cold, worker bees must shift from production tasks to maintenance tasks like fanning or shivering, directly reducing the amount of surplus honey the colony can create.

The core principle is simple: bee energy is a finite resource. A beekeeper's goal is to create conditions where the colony can allocate the maximum amount of energy toward honey production rather than simple survival against heat or cold.

The Hive's Energetic Budget

A honeybee colony operates like a finely tuned engine, constantly working to maintain thermal homeostasis. This balance is not just for comfort; it is essential for the colony's survival and productivity.

The Critical Brood Nest Temperature

For a colony to raise the next generation of bees, the brood nest—where the queen lays eggs and larvae develop—must be kept at a stable 34-35°C (93-95°F).

Deviations from this narrow range can harm or kill developing bees. The entire workforce will prioritize maintaining this temperature above all else, including honey production.

The Cost of Climate Control

Every action a bee takes consumes energy, which is fueled by honey and nectar. When bees are forced to regulate temperature, they are spending the very currency they are supposed to be storing.

This creates a direct trade-off. Energy spent on fanning to cool the hive or shivering to generate heat is energy that cannot be used to forage for nectar, process it into honey, or build wax comb.

How Bees Battle the Heat

When the external temperature rises, the hive can quickly overheat, especially in direct sunlight. The colony employs several clever strategies to cool down, all of which come at a cost to honey production.

Fanning and Air Circulation

Worker bees will align themselves at the hive entrance and throughout the hive, fanning their wings in unison. This creates a current of air that draws cooler air in and pushes hot, stale air out.

Evaporative Cooling

If fanning isn't enough, bees will switch to evaporative cooling. Foragers will collect water instead of nectar, bring it back to the hive, and spread thin layers of it on the surfaces of the comb. The fanning bees then evaporate this water, creating a powerful cooling effect, much like a swamp cooler.

Bearding

During intense heat, you may see a large number of bees hanging on the outside of the hive in a dense cluster that resembles a beard. This "bearding" reduces the number of bees inside the hive, lowering the internal metabolic heat load and improving air circulation. While this is a normal behavior, it means a significant portion of the workforce is idle, not producing honey.

The Hidden Dangers of Cold

While we often associate honey production with summer, the cold season has an equally significant, though less direct, impact on your harvest.

The Winter Cluster

As temperatures drop, bees form a tight cluster to conserve warmth. The bees on the inside of the cluster generate heat by rapidly vibrating their flight muscles—essentially shivering—while the bees on the outside act as a thick layer of insulation.

Fueling the Furnace

This shivering requires an immense amount of energy, which is fueled by one thing: stored honey. The colder the hive, the more honey the bees must consume simply to stay alive. A poorly insulated hive in a cold climate can burn through its winter stores, leaving no surplus for the beekeeper.

Reduced Brood Rearing

If temperatures remain low, the queen will slow or completely stop laying eggs. This conserves resources but also means the colony's population will be smaller in the spring, potentially delaying the buildup of a strong foraging force when the first nectar flows begin.

Understanding the Trade-offs for the Beekeeper

As a beekeeper, your role is not to control the weather but to mitigate its effects on the colony. This involves balancing competing needs.

Ventilation vs. Insulation

The primary trade-off is between ventilation and insulation. In summer, you need adequate ventilation to help the bees cool the hive and prevent overheating. However, that same ventilation can be a fatal source of heat loss in the winter.

Intervention vs. Natural Behavior

While it's tempting to intervene constantly, it's important to recognize that bees are experts at temperature control. Your job is to provide a good environment and the right equipment, not to manage the hive's thermostat directly. Excessive inspections, for example, can break the hive's propolis seals and disrupt their thermal regulation.

Site Selection is Your First Defense

The most impactful decision you make is where you place your hive. A location that receives morning sun to warm the hive but offers dappled shade during the hottest part of the afternoon is ideal. A natural windbreak can drastically reduce heat loss in the winter.

How to Support Your Colony's Temperature Control

Your goal is to reduce the energetic burden of temperature regulation on your bees. By taking a few key steps, you can help them focus on what they do best.

- If your primary focus is maximizing honey surplus in summer: Ensure your hive has a ventilated top cover, a nearby water source, and access to afternoon shade to minimize cooling stress.

- If your primary focus is ensuring winter survival: Provide your hive with a windbreak, consider using a hive wrap for insulation in cold climates, and ensure there is a small upper entrance for moisture to escape.

- If you are a new beekeeper establishing a hive: Prioritize site selection above all else, as a good location that balances sun and shade will solve many temperature-related problems for you.

By understanding and supporting your colony's natural efforts, you shift their energy from survival to production, resulting in a healthier hive and a more abundant harvest.

Summary Table:

| Temperature Stress | Bee Response | Impact on Honey Production |

|---|---|---|

| Heat | Fanning, water collection, bearding | Less foraging, energy spent on cooling |

| Cold | Shivering in a winter cluster | Stored honey consumed for warmth, less surplus |

| Brood Nest Deviation | Prioritizing brood temperature stability | Diverted workforce from honey-making tasks |

Maximize your apiary's productivity with the right equipment. Temperature management starts with a well-designed hive. HONESTBEE supplies durable, weather-appropriate beekeeping supplies and equipment to commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors through our wholesale-focused operations. Let us help you equip your hives for optimal thermal regulation, so your bees can focus on producing honey.

Contact HONESTBEE today to discuss your wholesale needs and boost your honey yield.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 10L Stainless Steel Electric Honey Press Machine

- Stainless Steel Manual Honey Press with Guard for Pressing Honey and Wax

- HONESTBEE Advanced Ergonomic Stainless Steel Hive Tool for Beekeeping

- Classic Wooden Bee Brush with Double-Row Boar Bristles

- HONESTBEE Premium Italian Style Hive Tool with Hardwood Handle

People Also Ask

- What are the key features of a honey press? Maximize Yield with Durable, Efficient Extraction

- What voltage options are available for stainless steel screw honey pumps? Choose the Right Power for Your Scale

- How does pressed honey compare to extracted or crush-and-strain? Unlock the Full Flavor of the Hive

- What are the key features of the stainless steel honey press? Maximize Yield & Guarantee Purity

- What are the advantages of using industrial-grade stainless steel honey extractors vs. traditional methods?