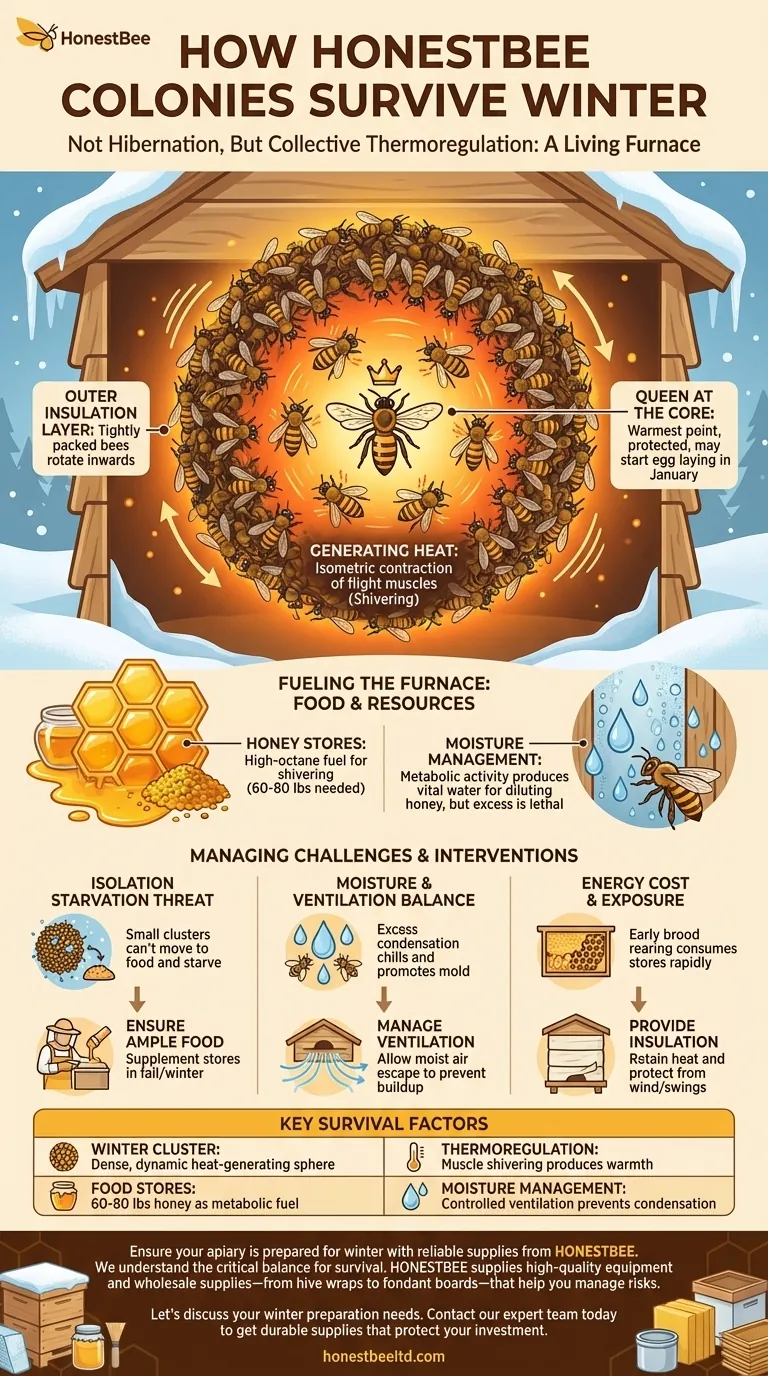

To put it simply, honey bee colonies survive winter not by hibernating, but by forming a dense cluster and actively generating their own heat. This "winter cluster" functions like a living furnace, shivering to maintain a stable temperature around the queen while slowly consuming the honey and pollen stores they gathered during the warmer months. It is an active, energy-intensive feat of collective thermoregulation.

The survival of a honey bee colony through winter is a delicate balance. It hinges on the colony's ability to convert stored food into metabolic heat within an insulating cluster, while carefully managing internal moisture and relying on sufficient population size to endure months of cold.

The Winter Cluster: A Living Furnace

The core of winter survival is the formation of the "winter cluster." This is not a passive huddle but a highly organized and dynamic structure.

Generating Heat Through Vibration

Bees don't wear coats; they create their own warmth. They do this by anchoring their wings and engaging in isometric contraction of their powerful flight muscles, essentially shivering intensely.

This constant vibration converts the chemical energy stored in honey directly into thermal energy, heating the interior of the cluster.

A Dynamic, Insulating Sphere

The cluster is structured like a sphere, with bees packed tightly on the outer layer to act as insulation, protecting the bees on the inside.

Bees are in constant, slow motion, with colder bees from the outer shell rotating inward to warm up and feed, while warmer bees from the interior move to the outer edge to take their turn as insulators.

The Queen's Role at the Core

The queen bee is always located at the warmest part of the cluster's center. The colony's primary goal is to keep her and the surrounding brood safe.

Remarkably, the queen often begins to lay eggs as early as January. This ensures the colony can begin replenishing its population and be ready for the first spring blooms.

Fueling the Furnace: Food and Water

A furnace is useless without fuel. For the winter cluster, that fuel is the honey and pollen meticulously stored throughout the previous season.

Honey as High-Octane Fuel

Honey is a dense carbohydrate, providing the massive amount of energy required for the bees to shiver and generate heat for months on end.

A strong, healthy colony typically requires 60 to 80 pounds of honey to successfully survive an average winter.

The Surprising Importance of Moisture

The bees' metabolic activity—respiration and processing honey—produces both heat and warm, humid air.

This humid air rises and condenses on cooler inner surfaces of the hive. The bees then collect this water, which is essential for diluting the thick, crystallized honey and for creating the "brood food" needed to feed new larvae.

A Slow Ascent to Sustenance

As winter progresses, the entire cluster slowly moves upwards through the hive. They do this to stay in constant contact with their remaining honey stores, which are typically located above where they first clustered.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Dangers

Winter survival is fraught with peril, and a colony's success depends on navigating several key challenges where the solution to one problem can create another.

The Threat of Isolation Starvation

A cluster that is too small may not have enough bees to move collectively. It can become "stuck" in one place and starve to death, even with frames of honey just a few inches away, because it's too cold for the cluster to break and move.

Moisture: A Double-Edged Sword

While some condensed moisture is vital, too much is lethal. If ventilation is poor, excess condensation can drip down onto the cluster, chilling the bees, promoting mold growth, and spreading disease.

The Energy Cost of Brood Rearing

Starting to raise brood in late winter is a gamble. It gives the colony a head start for spring but dramatically increases their consumption of honey and pollen at a time when their resources are at their lowest. A late-season cold snap can be devastating.

The Beekeeper's Role: Tipping the Scales

Modern beekeepers often intervene to help colonies navigate winter's challenges, essentially providing insurance against extreme conditions.

Ensuring Ample Food Stores

If a colony hasn't stored enough honey, a beekeeper will supplement their food in the fall with sugar syrup or provide solid food like fondant during the winter.

Providing Insulation and Windbreaks

Many beekeepers wrap their hives in black insulating material. This doesn't heat the hive but helps retain the heat the bees generate, reduces wind exposure, and protects the colony from rapid temperature swings.

Managing Ventilation

Proper hive management includes providing a small upper entrance. This allows the warm, moisture-laden air to escape, preventing the dangerous buildup of condensation inside the hive.

How to Apply This Understanding

Your perspective on winter survival changes depending on your goal.

- If your primary focus is the biology: View the winter cluster as a true superorganism, where individual bees act as cells in a larger body dedicated to collective thermoregulation.

- If your primary focus is practical beekeeping: Recognize your job is to mitigate the three primary threats: starvation (by ensuring enough food), moisture (by ensuring ventilation), and exposure (by providing insulation).

- If your primary focus is supporting pollinators: Plant a variety of late-blooming flowers in your garden to help bees build up the robust winter food stores they need to survive on their own.

Ultimately, the honey bee colony's ability to survive winter is a testament to its remarkable efficiency and collective coordination.

Summary Table:

| Key Survival Factor | Role in Winter Survival |

|---|---|

| Winter Cluster | A dense, dynamic sphere of bees that generates and retains heat. |

| Food Stores | 60-80 lbs of honey are consumed as fuel for metabolic heat generation. |

| Thermoregulation | Bees shiver by contracting flight muscles to produce warmth. |

| Moisture Management | Controlled ventilation prevents lethal condensation while providing essential water. |

Ensure your apiary is prepared for winter with reliable supplies from HONESTBEE.

As a commercial apiary or equipment distributor, your success depends on healthy, thriving colonies year-round. We understand the critical balance of food, insulation, and ventilation needed for winter survival. HONESTBEE supplies the high-quality beekeeping equipment and wholesale supplies—from hive wraps to fondant boards—that help you manage these risks effectively.

Let's discuss your winter preparation needs. Contact our expert team today to get the durable, dependable supplies that protect your investment through the coldest months.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Beekeeping Gloves Goatskin Leather with Long Cotton Sleeve for Beekeepers

- Plastic Handle Single Row Artificial Fiber Bee Brush

- Wooden Bee Brush with Double-Row Horsehair Bristles

- Premium Ventilated Goatskin Beekeeping Gloves with Full 3-Layer Mesh Sleeve

- Professional Galvanized Hive Strap with Secure Locking Buckle for Beekeeping

People Also Ask

- How should beekeeping gloves be maintained? Protect Your Investment and Dexterity

- Why is dexterity and flexibility important in beekeeping gloves? Boost Your Hive Management Efficiency

- What are the steps to clean cow leather beekeeping gloves? Protect Your Investment & Hive Health

- Why is it important to clean beekeeping gloves? Protect Your Hives & Extend Equipment Life

- What might experienced beekeepers prefer regarding gloves? Prioritizing Dexterity Over Protection