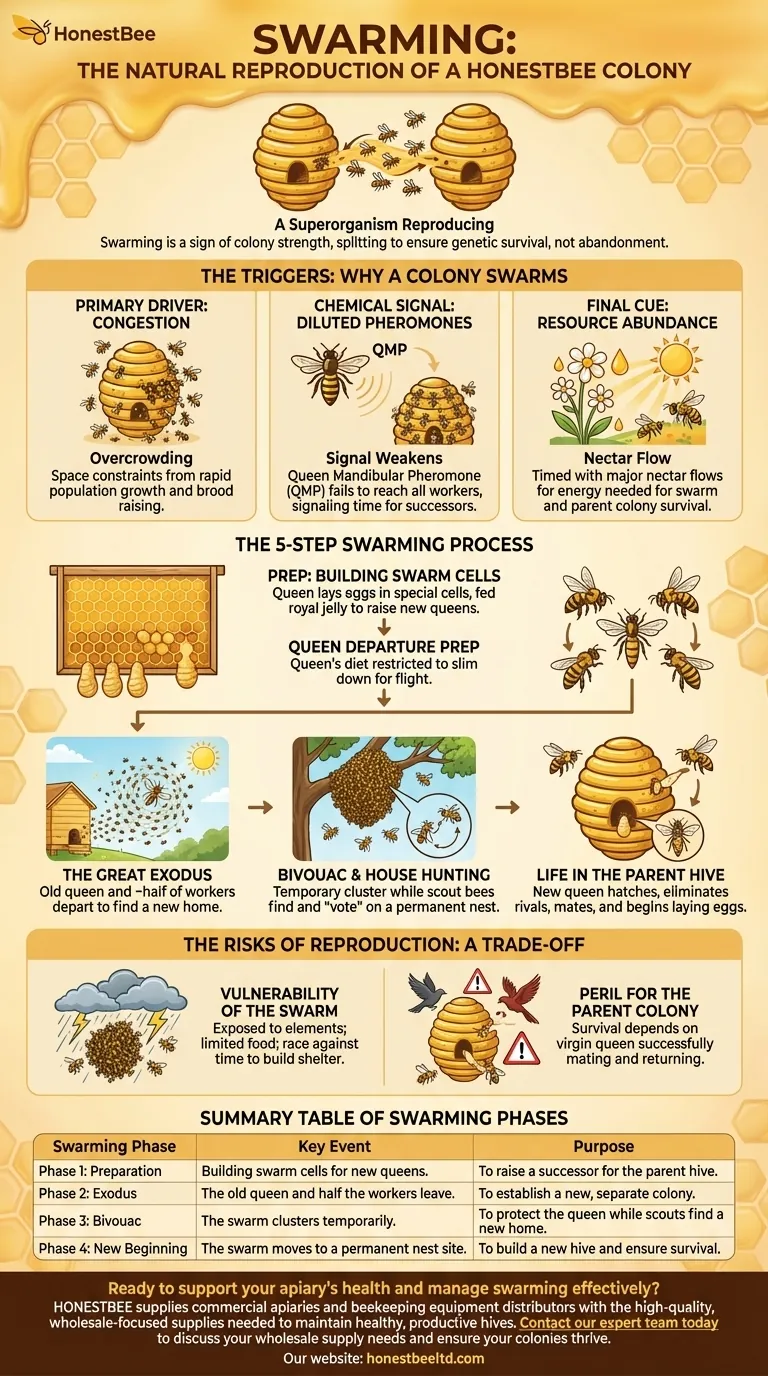

At its core, swarming is the natural process of honey bee colony reproduction. When a hive becomes overcrowded, the original queen bee leaves with roughly half of the worker bees to establish a new colony. Before they depart, the workers remaining in the original hive have already prepared to raise a new queen who will take her mother's place.

Swarming should not be viewed as a colony abandoning its home, but as a single superorganism successfully reproducing. It is a sign of a colony's strength and vitality, splitting into two distinct entities to ensure the survival of its genetics.

The Triggers: Why a Colony Decides to Swarm

A colony doesn't swarm on a whim. The decision is driven by a combination of clear environmental and biological signals that indicate the time is right for reproduction.

The Primary Driver: Congestion

The most significant trigger for swarming is overcrowding. As a healthy queen lays up to 2,000 eggs per day, the hive population can expand rapidly in the spring.

When bees run out of space to raise brood, store pollen, and cure nectar, the entire hive becomes congested. This physical constraint is the primary signal that the colony has outgrown its current home.

The Chemical Signal: Diluted Pheromones

A queen bee produces a unique chemical signature known as Queen Mandibular Pheromone (QMP). This pheromone is passed throughout the colony from bee to bee, acting as a social glue that signals her presence and suppresses the workers' ability to raise new queens.

In a large, congested hive, the QMP becomes diluted and doesn't reach all workers effectively. This weakening signal tells the colony that the queen's influence is waning and that it is time to create successors.

The Final Cue: An Abundance of Resources

Swarming is an energy-intensive process that requires a strong workforce and ample food. Colonies instinctively time their swarm preparations to coincide with a major nectar flow.

This ensures that both the departing swarm and the original parent colony have access to the resources needed to build up their populations and food stores before the next winter.

The Step-by-Step Swarming Process

Once the triggers are met, the colony begins a highly organized and fascinating sequence of events.

Phase 1: Building Swarm Cells

The first visible sign of swarm preparation is the construction of swarm cells. These are special, peanut-shaped wax cells, typically built along the bottom edge of the honeycomb frames.

The queen lays fertilized eggs in these cells. The workers feed the resulting larvae a rich diet of royal jelly, which is what allows them to develop into new queens instead of workers.

Phase 2: The Queen's Departure Prep

An egg-laying queen is too heavy to fly long distances. In the days leading up to the swarm, worker bees will restrict her diet and chase her around the hive.

This forced exercise causes her to slim down, making her light enough for the journey to a new home.

Phase 3: The Great Exodus

On a warm, sunny day, the swarm emerges. The old queen and tens of thousands of worker bees pour out of the hive entrance in a massive, swirling cloud of bees.

The sound and sight can be intimidating, but the bees are remarkably docile at this stage. Their primary focus is on protecting their queen and finding a new home.

Phase 4: The Bivouac and House Hunting

The swarm will fly a short distance and settle in a temporary cluster, or bivouac, on a nearby tree branch or structure. From this cluster, hundreds of scout bees fly out in search of a suitable cavity for a permanent nest.

Scouts return and perform a "waggle dance" to communicate the location and quality of potential sites. The bees democratically "vote" on the best option before the entire cluster takes flight to its new home.

Phase 5: Life in the Parent Hive

Back in the original hive, the remaining bees continue their work. About a week after the swarm departed, the first new queen will hatch from her swarm cell. Her first act is to locate and eliminate any other rival queens still developing in their cells. She then embarks on a mating flight and returns to begin her life as the new mother of the colony.

Understanding the Trade-offs: The Risks of Reproduction

While swarming is a natural and necessary process, it is fraught with risk for both the swarm and the parent colony.

Vulnerability of the Swarm

The swarm cluster is completely exposed to the elements. A sudden storm or cold snap can be fatal. They have limited food reserves—only the honey the bees carry in their stomachs—and are in a race against time to find shelter and begin building comb.

Peril for the Parent Colony

The original colony is left with a smaller population and, for a period, no egg-laying queen. Their survival depends entirely on their virgin queen successfully mating and returning to the hive. If she is eaten by a bird or fails to return from her mating flight, the colony is doomed.

How to Interpret Swarming

Understanding the purpose of swarming is key to knowing how to react, whether you are a beekeeper or simply an observer.

- If your primary focus is honey production: Swarming must be managed. Preventing a swarm retains a large workforce in a single hive, which is necessary to collect a surplus honey crop.

- If your primary focus is increasing colony numbers: Capturing a swarm is an excellent way to start a new hive with a proven, healthy queen and a dedicated workforce.

- If your primary focus is conservation: Recognizing that a swarm is a natural sign of a healthy bee population is crucial. They are not aggressive and should be left to a professional beekeeper to be collected and re-homed safely.

Ultimately, the act of swarming is the pinnacle of the honey bee colony's success—a testament to its ability to thrive and replicate itself against all odds.

Summary Table:

| Swarming Phase | Key Event | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Preparation | Building swarm cells for new queens. | To raise a successor for the parent hive. |

| Phase 2: Exodus | The old queen and half the workers leave. | To establish a new, separate colony. |

| Phase 3: Bivouac | The swarm clusters temporarily. | To protect the queen while scouts find a new home. |

| Phase 4: New Beginning | The swarm moves to a permanent nest site. | To build a new hive and ensure survival. |

Ready to support your apiary's health and manage swarming effectively?

Swarming is a sign of a strong colony, but managing it is crucial for honey production and hive stability. HONESTBEE supplies commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors with the high-quality, wholesale-focused supplies needed to maintain healthy, productive hives. From hive components to protective gear, we provide the reliable equipment that supports your beekeeping success.

Contact our expert team today to discuss your wholesale supply needs and ensure your colonies thrive.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- HONESTBEE Advanced Ergonomic Stainless Steel Hive Tool for Beekeeping

- Full Set Beekeeping Electronic Bee Venom Collector Machine Device for Bee Venom Collecting

- No Grafting Queen Rearing Kit: System for Royal Jelly Production and Queen Rearing

- White PVC Beekeeping Shoes with Non-Slip Safety Sole

- Beehive Handle and Frame Rest Cutting Machine: Your Specialized Hive Machine

People Also Ask

- What are the basic tools for beekeeping? Essential Starter Kit for Safe & Successful Hive Management

- What is the hole in a hive tool for? A Multi-Tool for Apiary Repairs and Maintenance

- Why is it important to compare the progress of different hives? A Beekeeper's Key Diagnostic Tool

- What are the specific applications of a beekeeping chisel? Master Hive Maintenance with Precision Tools

- What is the significance of professional hive-making tools? Scale Your Stingless Bee Farm with Precision Equipment