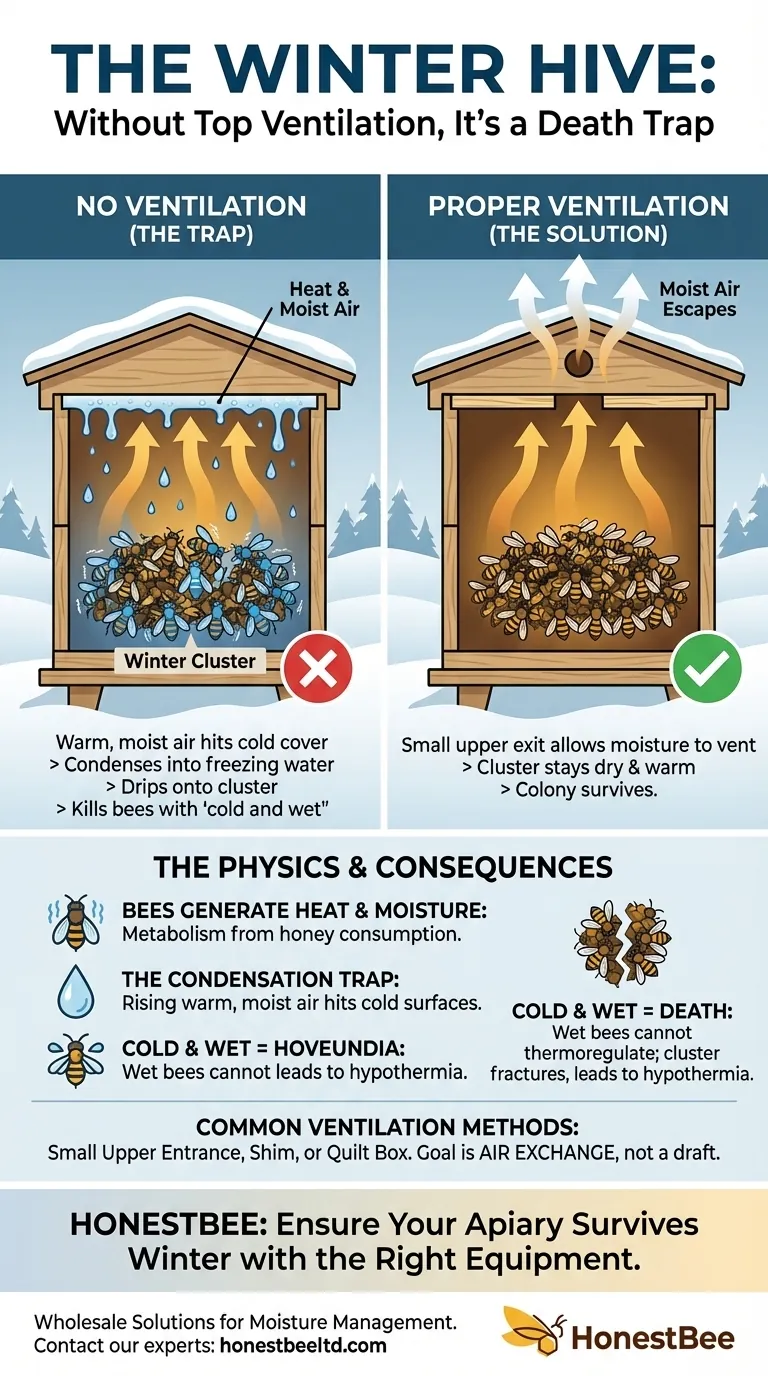

Without proper top ventilation in winter, your beehive effectively becomes a death trap. The warm, moist air from the bees' respiration rises, hits the cold inner cover, and turns into condensation. This condensation then drips as freezing cold water onto the bee cluster below, killing them not from the ambient cold, but from being cold and wet.

The central challenge of overwintering a hive is not temperature, but moisture management. A lack of top ventilation traps metabolic moisture, creating deadly internal "rain" that is far more dangerous to a colony than external cold.

The Physics of a Winter Hive

To understand why ventilation is critical, you must first understand the environment inside a winter hive. It is a delicate balance of heat generation and its dangerous byproduct: water.

How Bees Generate Heat

Bees survive the cold by forming a tight winter cluster. They generate heat by shivering their flight muscles, collectively keeping the center of the cluster warm enough for the queen and surrounding bees to survive.

To fuel this activity, they consume their stored honey reserves throughout the winter.

The Byproduct of Survival: Respiration

Like any living organism, a bee's metabolism produces byproducts. As they consume honey, their respiration releases heat, carbon dioxide, and a significant amount of warm, moist air.

The Condensation Trap

This warm, water-laden air rises. When it makes contact with the cold inner surface of the hive cover—which is chilled by the outside winter air—it condenses into water droplets.

Without an escape route, these droplets accumulate and eventually drip down, right onto the cluster of bees working so hard to stay warm and alive.

Why "Cold and Wet" is a Death Sentence

A dry bee can withstand remarkably low temperatures. A wet bee cannot. The introduction of cold water to the cluster is catastrophic.

The Impact on the Winter Cluster

A steady drip of cold water can cause the bees to break their tight cluster formation. A fractured cluster loses its ability to generate and conserve heat efficiently, making the entire colony vulnerable.

The Inability to Thermoregulate

When a bee becomes wet, its body can no longer effectively regulate its temperature. It chills rapidly and dies from hypothermia, even at temperatures it could otherwise easily survive.

It's Not the Cold, It's the Wetness

This is the most critical principle to understand. A strong, dry colony can survive a harsh, frozen winter. That same colony, if subjected to internal condensation drips, will perish even in a milder, damp winter.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The goal of ventilation is often misunderstood. It is not about letting cold air in, but about letting moist air out.

The Fear of "Too Much" Ventilation

Beekeepers rightly worry that a large opening will let too much precious heat escape, creating a draft and forcing the bees to consume more honey to stay warm.

The Goal is Air Exchange, Not a Draft

Effective winter ventilation does not require a large, drafty hole. It requires a small, high-placed exit that allows the naturally rising warm, moist air to escape passively.

This minimal air exchange is enough to carry away the water vapor before it can condense, without causing a significant loss of heat from the core of the cluster.

Common Ventilation Methods

Simple solutions like propping the inner cover up with a small shim, or using an upper entrance (a 1-inch hole drilled in the top box), are often sufficient. More advanced methods like a quilt box use wood shavings to absorb moisture while providing an exit path.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your ventilation strategy should balance the absolute need for moisture removal with the desire for heat retention.

- If your primary focus is simplicity and proven effectiveness: Provide a small upper entrance (3/4" to 1" diameter) or crack the outer cover to create a small gap for moist air to escape.

- If your primary focus is maximum moisture control in a damp climate: Use a quilt box or a dedicated moisture board above the cluster to absorb condensation and vent it away.

- If your primary concern is heat loss in a frigid climate: Ensure the ventilation opening is small and positioned to prevent a direct draft through the cluster.

Ultimately, ensuring your bees are dry is the single most important factor for their winter survival.

Summary Table:

| Problem | Cause | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Condensation Drip | Moist air from bee respiration hits cold inner cover | Cold water drips onto bee cluster, causing hypothermia and death |

| Fractured Cluster | Bees break formation due to cold water drip | Loss of heat generation and conservation, leading to colony collapse |

| Moisture Trap | Lack of top ventilation prevents moist air escape | Internal 'rain' becomes more dangerous than external cold |

Ensure your apiary survives the winter with the right equipment from HONESTBEE. We supply commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors with durable, well-designed supplies that promote proper hive ventilation and moisture management. Don't let condensation risk your colony's survival—contact our experts today to discuss wholesale solutions tailored for large-scale beekeeping success.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Stainless Steel Round Beehive Air Vents for Ventilation

- Long Langstroth Style Horizontal Top Bar Hive for Wholesale

- Professional Insulated Winter Hive Wrap for Beekeeping

- Inner Beehive Cover for Beekeeping Bee Hive Inner Cover

- Professional Galvanized Hive Strap with Secure Locking Buckle for Beekeeping

People Also Ask

- What is the key to thriving in beekeeping during challenging winters? Master the Heat-Moisture Balance

- How is the inner cover used to promote ventilation? Master Hive Climate Control for Healthy Bees

- What factors ensure bees stay warm and healthy during winter? Master the 3 Keys to Hive Survival

- Why might beekeepers use an inner cover under the telescoping outer cover? Simplify Hive Management & Protect Your Colony

- What purpose does covering the hive top with plastic film serve? Maintain Hive Humidity in Arid Regions