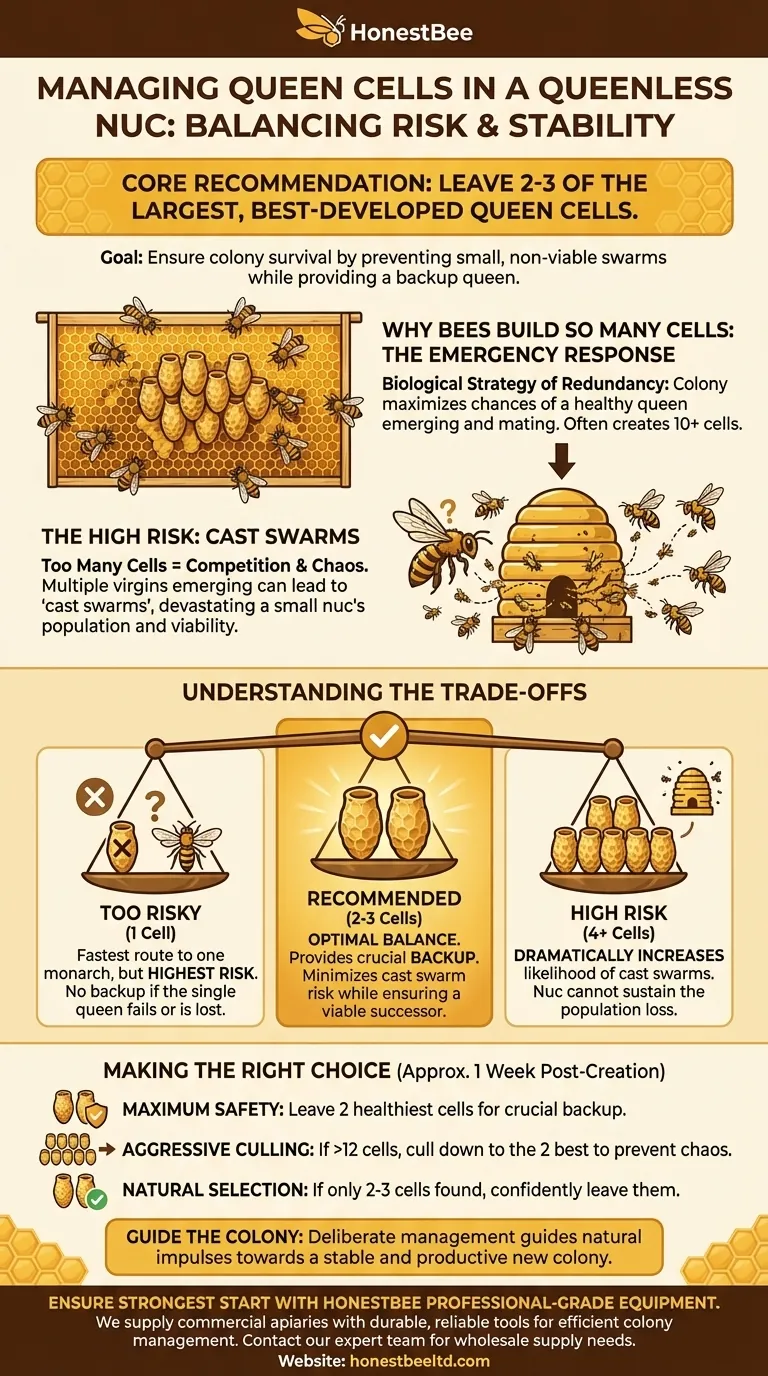

In a queenless nuc, you should leave two to three of the largest and best-developed queen cells. This culling process is typically done about a week after the nuc is created. By reducing the number of potential queens, you prevent the colony from issuing small, non-viable swarms while still providing a backup in case the first queen fails to emerge or mate successfully.

Your goal is not just to create a new queen, but to ensure the stability and survival of the entire nucleus colony. Limiting the number of queen cells balances the bees' natural emergency response against the practical risk of the colony swarming itself into oblivion.

Why Bees Build So Many Queen Cells

When a honeybee colony suddenly loses its queen, it enters a state of emergency. The absence of the queen's pheromones signals to the worker bees that the survival of the colony is at stake.

The Emergency Response

To maximize the chances of successfully raising a successor, the workers will create a large number of queen cells—often ten or more. They build these special, peanut-shaped cells over existing female larvae that are young enough to be developed into queens.

A Strategy of Redundancy

This isn't a sign of confusion; it's a biological strategy. By starting numerous potential queens, the colony increases the odds that at least one will emerge healthy, win the right to rule, and mate successfully to secure the colony's future.

The High Risk of Leaving Too Many Cells

While building many cells is the bees' best survival strategy, leaving them all in place is a significant risk for the beekeeper managing a small nuc. The primary danger is the creation of "cast swarms."

The Race for Dominance

The first virgin queen to emerge will typically move to the other queen cells and attempt to sting and kill her unborn rivals. However, this process isn't always perfect.

The Danger of Cast Swarms

If two or more virgin queens emerge around the same time, the colony can become chaotic. The bees may follow the first queen out of the hive in a primary swarm, and then a second group may leave with another virgin queen in a secondary, or "cast," swarm.

For a small nucleus colony, losing a cast swarm is devastating. It depletes the nuc of a significant portion of its worker bees and one of its viable queens, leaving the remaining colony too weak to thrive.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Deciding how many cells to leave involves balancing risk against security. Your choice directly impacts the probability of success for the nuc.

The Risk of Leaving Only One Cell

Leaving a single queen cell is the fastest way to establish a single monarch, but it carries the highest risk. If that cell is not viable, the queen emerges with a defect, or she is lost on her mating flight, the colony will be hopelessly queenless with no backup plan.

The Risk of Leaving More Than Three Cells

As the references confirm, leaving four or more queen cells dramatically increases the likelihood of cast swarms. The bees' instinct to swarm with extra queens is strong, and a small nuc does not have the population to sustain such a split.

The Logic of Leaving Two or Three

Leaving two or three of the largest, best-formed cells provides the perfect balance. It gives the colony insurance. If the first queen to emerge fails, a second is ready to take her place. This redundancy is critical, but the number is low enough to minimize the instinct for the colony to issue a cast swarm.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

When you inspect your queenless nuc about a week after its creation, be deliberate in your selection. You are guiding the colony toward a stable outcome.

- If your primary focus is maximum safety: Leave two of the largest, healthiest-looking cells to provide a crucial backup without significantly increasing swarm risk.

- If your colony has built over a dozen cells: This is a strong emergency response; cull aggressively down to the two best cells to impose order and prevent chaos.

- If you find only two or three cells: The bees may have already selected the best larvae; you can confidently leave them as they are.

By managing queen cells deliberately, you guide the colony's natural impulses toward the creation of a stable and productive new colony.

Summary Table:

| Action | Number of Queen Cells | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Recommended | 2 to 3 | Balances risk: provides a backup queen while minimizing cast swarms. |

| Too Risky | 1 | No backup if the single queen fails. |

| High Risk | 4+ | Significantly increases the chance of devastating cast swarms. |

Ensure your nucs have the strongest start with professional-grade equipment from HONESTBEE.

Managing queen cells is a delicate balance, and having the right supplies is crucial for success. We supply commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors with the durable, reliable tools needed for efficient colony management. From nuc boxes to protective gear, our wholesale-focused operations ensure you get the quality equipment your operation depends on.

Contact our expert team today to discuss your wholesale beekeeping supply needs and secure the foundation for your colonies' success.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Brown Nicot Queen Cell Cups for Breeding Queen Bees Beekeeping

- High Performance Plastic Queen Excluder for Beekeeping and Apiary Management

- 5 Frame Wooden Nuc Box for Beekeeping

- Classic Wooden and Mesh California Queen Cage

- Queen Bee Marking Pen POSCA Queen Marking Pens for Beekeeping Bee Markers

People Also Ask

- What role does the natural swarming process play in queen rearing? Harness the Swarm Instinct for Better Queens

- What is the impact of 3D printing precision on polycarbonate queen cell cups? Achieving Higher Acceptance Rates

- Why are durable standardized beekeeping tools essential for green production? Unlock Sustainable Economic Growth

- How many cells are given to a nucleus? Understand the One-to-One Rule in Cell Biology

- How does Queen Rearing with JZBZ work? A Reliable System for Consistent Queen Production