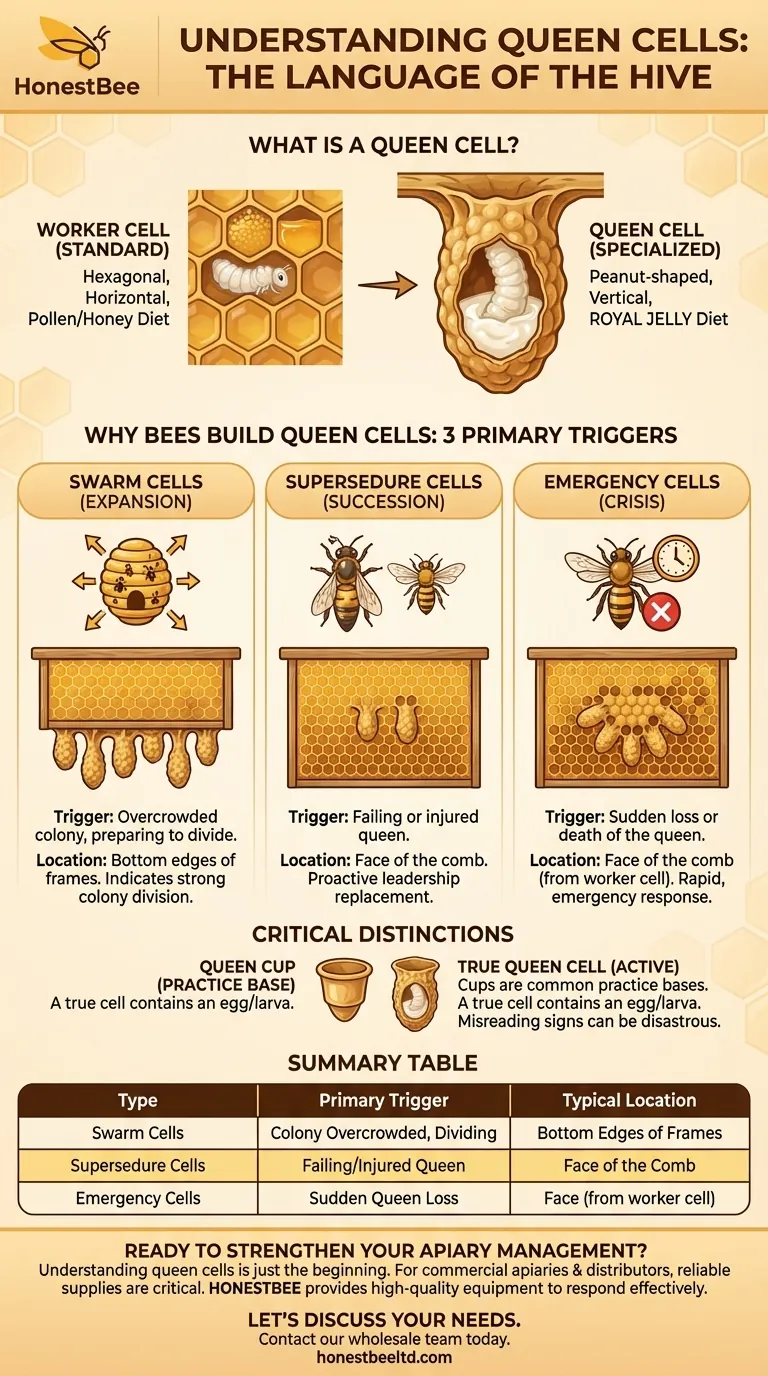

In short, a queen cell is a specialized, peanut-shaped beeswax cell built by worker bees for the sole purpose of raising a new queen. Unlike standard hexagonal cells, queen cells are built vertically with the opening facing downwards, and they are typically located on the edges or the main surface of the comb.

The presence of a queen cell is one of the most significant signals a honeybee colony can send. Its location and number reveal the bees' plan for the future, whether it's expanding the colony, replacing a failing leader, or responding to a sudden crisis.

The Purpose of a Queen Cell

A standard honeycomb cell is a small, horizontal hexagon used for raising worker or drone bees or for storing honey and pollen. A queen cell is fundamentally different in both its construction and its purpose.

A Unique Structure

Worker bees construct queen cells from beeswax, giving them a distinct, rough texture resembling a peanut shell. They are significantly larger than worker cells to accommodate the development of a queen bee.

A Special Diet

The larva inside a queen cell is fed exclusively on a diet of royal jelly. This protein-rich substance is what triggers the larva's development into a fertile queen rather than a sterile worker bee.

Reading the Hive: Why Bees Build Queen Cells

The reason a colony builds queen cells is the most crucial piece of information for a beekeeper. There are three primary triggers, and the location of the cells can be a strong clue.

Swarm Cells: The Signal for Expansion

When a colony becomes too crowded, the bees prepare to swarm, which is their natural method of reproduction. They build multiple queen cells, often between five and twenty or more.

These swarm cells are typically found hanging from the bottom edges of the frames. Their presence indicates a strong, healthy colony is preparing to divide, with the old queen and about half the bees leaving to find a new home.

Supersedure Cells: A Planned Succession

If a queen is old, injured, or laying poorly, the colony will decide to replace her in a process called supersedure. They build only a few queen cells, usually just one to three.

These supersedure cells are most often located on the face of the comb, not along the bottom edge. This is a sign of a colony proactively managing its own health and leadership.

Emergency Cells: A Response to Crisis

If a queen is suddenly lost or killed, the colony must act fast to create a replacement. This is an emergency situation.

Worker bees will select several existing worker larvae (less than three days old) and build emergency queen cells around them. Like supersedure cells, these are found on the face of the comb, distinguished by the fact that they are built out from a standard worker cell.

Common Misinterpretations and Pitfalls

Distinguishing between different queen cells—and knowing when to act—is a critical skill. Misreading the signs can lead to counterproductive actions.

Queen Cups vs. Queen Cells

Bees often build practice queen cell bases called queen cups. These are small, downward-facing cups, usually found along the bottom or edges of the comb. An empty cup is not a cause for concern; it's simply the bees being prepared. A queen cell is only a true cell once it contains an egg or larva.

The Danger of Destroying Cells

A common mistake is to destroy all queen cells on sight to prevent swarming. While this can work for swarm cells, destroying supersedure cells can be disastrous. If you destroy the colony's only chance to replace their failing queen without providing a new one, you risk the entire colony dying.

How to Respond When You Find Queen Cells

Your response should be guided by the type of cell you find and your goals for the hive.

- If your primary focus is preventing a swarm: You can carefully remove swarm cells from the bottom of the frames, but you must also address the underlying issue of overcrowding by providing more space or splitting the colony.

- If your primary focus is supporting a healthy succession: Allow the bees to proceed with supersedure by leaving the one or two cells on the face of the comb intact.

- If your primary focus is saving a queenless hive: Confirm that the emergency cells are viable (contain a healthy larva) and allow the bees to raise their new queen, or intervene by introducing a new mated queen.

Understanding queen cells is to understand the language of the hive, allowing you to work with your bees instead of against them.

Summary Table:

| Type of Queen Cell | Primary Trigger | Typical Location in Hive |

|---|---|---|

| Swarm Cells | Colony is overcrowded and preparing to divide. | Bottom edges of frames. |

| Supersedure Cells | Replacing an old, failing, or injured queen. | Face of the comb. |

| Emergency Cells | Sudden loss or death of the queen. | Face of the comb (built out from a worker cell). |

Ready to strengthen your apiary management?

Understanding queen cells is just the beginning. For commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors, having the right, reliable supplies is critical to managing colony health and preventing losses. HONESTBEE provides the high-quality beekeeping equipment and supplies you need to respond effectively to your hives' signals.

Let's discuss your needs. Contact our wholesale team today to ensure your operation is equipped for success.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Brown Nicot Queen Cell Cups for Breeding Queen Bees Beekeeping

- JZBZ Langstroth Queen Rearing Frame for Beekeeping

- JZBZ Push-In Queen Cell Cups for Beekeeping

- Clear Black Plain Polystyrene Queen Bee Grafting Cell Cups No Lug for Bee Queen Cup

- Plastic Chinese Queen Grafting Tool for Bee Queen Rearing

People Also Ask

- Why are durable standardized beekeeping tools essential for green production? Unlock Sustainable Economic Growth

- Why is it important to select a healthy larva less than 24 hours old for queen rearing? Maximize Queen Quality and Colony Strength

- How do specialized queen rearing and high-precision AI equipment influence overwintering? Boost Colony Survival Rates

- What is the advantage of the Nicot Cupkit system? Secure Your Queen Rearing Success with Batch Protection

- How does Queen Rearing with JZBZ work? A Reliable System for Consistent Queen Production