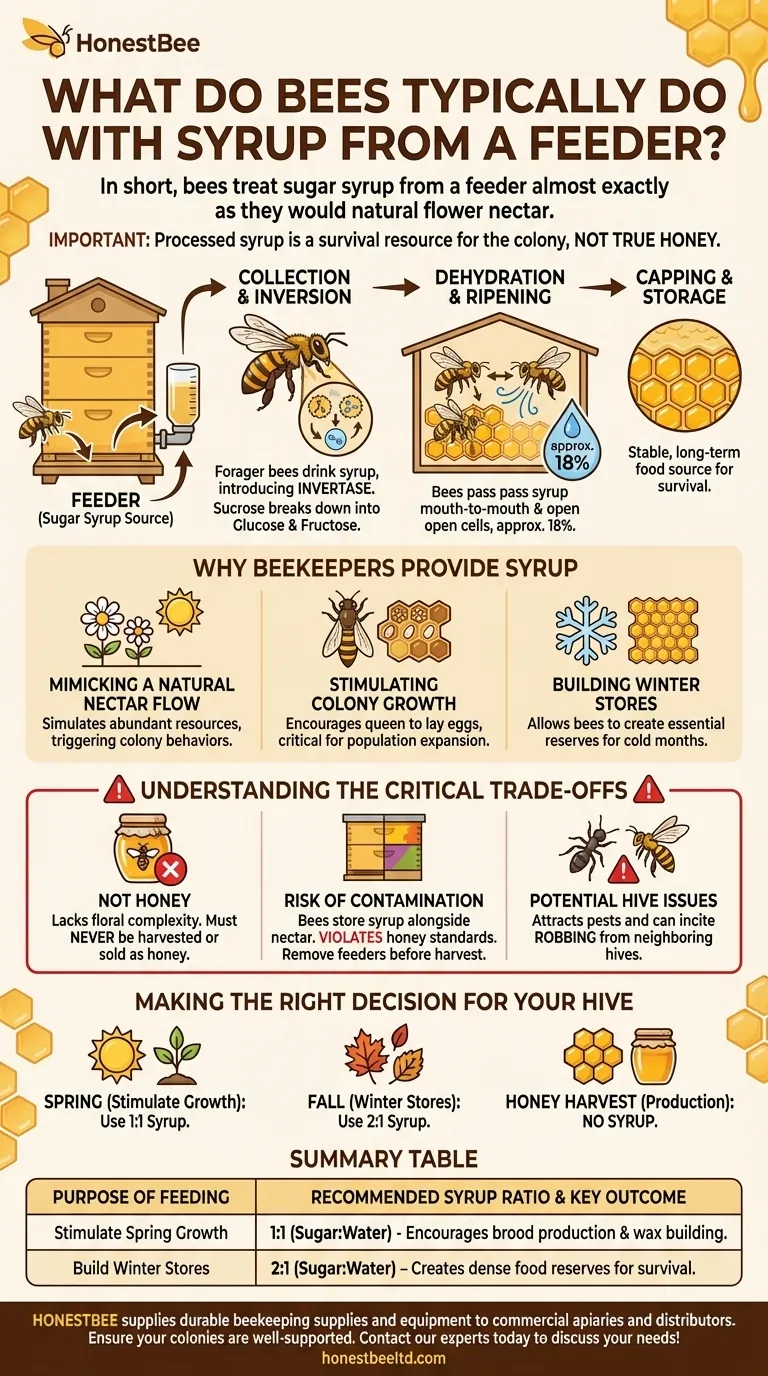

In short, bees treat sugar syrup from a feeder almost exactly as they would natural flower nectar. Foraging bees collect the syrup, transport it back to the hive, and pass it to house bees who begin a process of dehydration and enzymatic conversion before storing the finished product in honeycomb cells.

While bees process syrup into a storable food, this product is a survival resource for the colony, not true honey. Understanding this distinction between a management tool and a natural product is the core of responsible beekeeping.

Why Beekeepers Provide Syrup

Feeding bees sugar syrup is a strategic management technique used to support or stimulate a colony when natural resources are scarce. It is a substitute for nectar, not a replacement for honey.

Mimicking a Natural Nectar Flow

A feeder provides a concentrated, reliable source of carbohydrates. This simulates a "nectar flow," the period when abundant flowers are producing nectar.

This artificial flow signals to the colony that resources are plentiful, triggering specific behaviors.

Stimulating Colony Growth

The presence of incoming "nectar" encourages the queen to increase her rate of laying eggs. The colony interprets this abundance as the right time to expand its population, which is critical for new or weak hives.

Building Winter Stores

In the fall, after the last natural nectar flow has ended, beekeepers often feed a heavy syrup. This allows the bees to quickly create and cap the stores they will need to survive the cold winter months when they cannot forage.

The Journey from Feeder to Comb

The process bees use to convert syrup into a storable food mirrors the one they use for nectar. This involves chemical changes and dehydration.

Collection and Inversion

Forager bees drink the syrup and store it in their "honey stomach," or crop. Here, they introduce enzymes, most notably invertase, which begins breaking down the complex sucrose of table sugar into simpler, more digestible sugars: glucose and fructose.

Dehydration and Ripening

Back in the hive, the syrup is passed mouth-to-mouth between house bees. This action continues the enzymatic conversion and gradually reduces the water content.

Bees then deposit the partially ripened syrup into open honeycomb cells. They further dehydrate it by fanning their wings over the comb, creating airflow that evaporates moisture until it reaches approximately 18%—a level that prevents fermentation.

Capping and Storage

Once the syrup has been fully "ripened" to the correct moisture content, the bees seal the cell with a fresh wax cap. This creates the stable, long-term food source the colony will rely on later.

Understanding the Critical Trade-offs

Using syrup is a powerful tool, but it comes with significant responsibilities and potential pitfalls. It is not a shortcut to honey production.

The Key Distinction: It Is Not Honey

True honey is derived from the complex nectar of flowers. It contains unique pollen, proteins, minerals, and phytonutrients specific to the floral source.

Syrup-based stores lack this nutritional and chemical complexity entirely. It is a simple carbohydrate store for bee survival and must never be harvested and sold or labeled as honey.

Risk of Contaminating the Honey Harvest

If you feed a colony while also having honey supers on the hive intended for human consumption, the bees will store the syrup right alongside the nectar.

This contaminates the honey, diluting its quality and violating the standard of what can legally be called honey. Feeders must be removed when collecting honey for harvest.

Potential Hive Issues

Improperly managed feeders can attract pests like ants and wasps. A strong flow from a feeder can also incite "robbing," where bees from stronger neighboring hives attack the colony to steal the abundant food source.

Making the Right Decision for Your Hive

How and when you feed depends entirely on your goal for the colony.

- If your primary focus is establishing a new colony: Feed a light 1:1 syrup (sugar to water by weight) in the spring to stimulate brood production and rapid wax building.

- If your primary focus is preparing for winter: Feed a heavy 2:1 syrup in the fall to allow bees to quickly build up dense, life-sustaining food stores.

- If your primary focus is honey production for harvest: Do not feed syrup while honey supers are on the hive during a natural nectar flow.

Using syrup strategically empowers you to work with your bees, supporting their health and ensuring the colony's long-term survival.

Summary Table:

| Purpose of Feeding | Recommended Syrup Ratio | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulate Spring Growth | 1:1 (Sugar:Water) | Encourages brood production and wax building. |

| Build Winter Stores | 2:1 (Sugar:Water) | Creates dense food reserves for colony survival. |

Support your apiary's health and productivity with the right equipment. HONESTBEE supplies durable beekeeping supplies and equipment to commercial apiaries and distributors through wholesale-focused operations. Ensure your colonies are well-supported—contact our experts today to discuss your needs!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- HONESTBEE Round Hive Top Bee Feeder for Syrup

- Rapid Bee Feeder White Plastic 2L Round Top Feeder for 8 or 10-Frame Bee Hives

- Classic Boardman Entrance Bee Feeder Hive Front Feeding Solution

- Professional Hive Front Entrance Bee Feeder

- HONESTBEE Professional Hive Top Bee Feeder Feeding Solution

People Also Ask

- What are the features of top feeders for bees? Maximize Hive Health with Safe, High-Capacity Feeding

- What can the round hive top feeder be used for? A Guide to Efficient, Safe Bee Feeding

- How should the round hive top feeder be positioned? Master Internal Feeding for Stronger Colonies

- How should syrup for bees be prepared? Master the Ratio for a Thriving Hive

- What is a top feeder for bees? Maximize Colony Health with Efficient Feeding