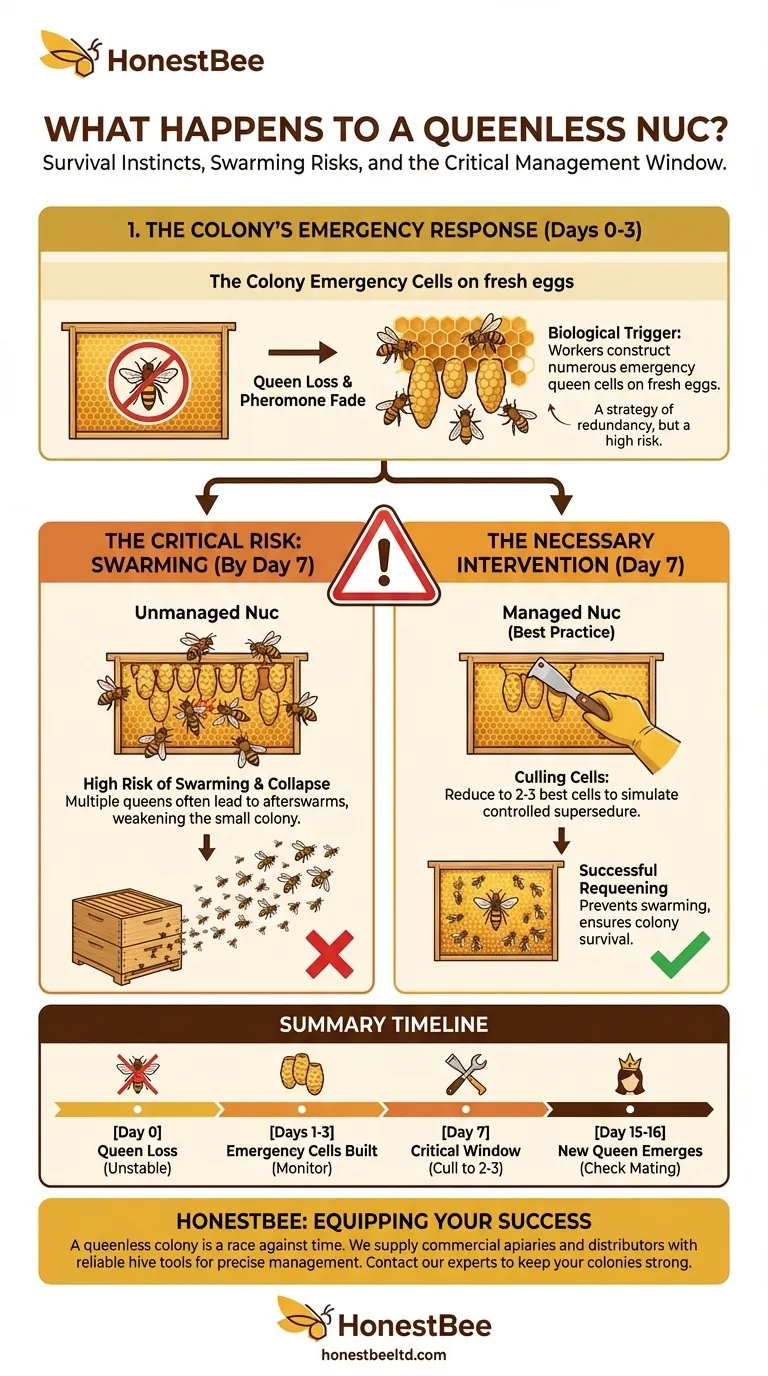

When a nuc becomes queenless, its survival instinct kicks into high gear. The worker bees will immediately begin constructing emergency queen cells on frames containing fresh eggs, their only means of creating a new queen. A queenless nuc will often build a surprising number of these cells—sometimes ten or more—as an insurance policy for the colony's future.

The core challenge is not that the bees won't try to raise a new queen, but that they will be too successful. An unmanaged queenless nuc with multiple queen cells is highly prone to swarming, which can deplete the small colony and risk its collapse.

The Colony's Emergency Response

A honey bee colony cannot survive for long without a laying queen. Her pheromones provide social cohesion, and her egg-laying is essential for replenishing the workforce. Her absence triggers a predictable and urgent chain of events.

The Biological Trigger

The moment a queen is removed or dies, her pheromones begin to fade. This chemical signal alerts the worker bees that the colony is in peril, initiating the emergency queen-rearing procedure.

Constructing Queen Cells

Worker bees identify several larvae that are just a few days old. They extend the wax cell downwards to create the distinctive peanut-shaped queen cell and begin feeding these chosen larvae a special, protein-rich diet of royal jelly. This unique diet is what transforms a standard female larva into a queen instead of a worker.

A Strategy of Redundancy

The colony builds numerous queen cells as a form of biological insurance. By starting many potential queens, they increase the odds that at least one will successfully emerge, take her mating flights, and return to the hive to begin laying.

The Critical Management Window

While the bees' instinct to create multiple queens is for survival, it introduces a significant risk for the beekeeper: swarming. This is especially dangerous for a small nucleus colony.

The Problem of Multiple Queens

The first virgin queen to emerge will typically seek out and destroy her rivals while they are still sealed in their cells. However, if two or more queens emerge at the same time, they may fight to the death.

The High Risk of Swarming

A more common outcome, especially if four or more queen cells are left intact, is the issuance of one or more "afterswarms." The first virgin queen to emerge may leave with a portion of the bees, and a subsequent queen may do the same. This severely weakens the nuc, leaving it with too few bees to thrive.

The Necessary Intervention

To ensure the nuc successfully requeens itself without self-destructing, the beekeeper must step in. The goal is to leverage the bees' natural process while mitigating the risk of swarming.

The Case for Culling Cells

The established best practice is to reduce the number of queen cells. This action simulates a more controlled "supersedure" event rather than a chaotic emergency, drastically lowering the swarm impulse.

When and How to Act

About one week after the nuc becomes queenless, you should inspect the frames. Carefully identify all the queen cells and select the two or three largest, best-formed ones to keep. Gently remove the others by scraping them off the comb.

Why Leave More Than One?

Leaving two or three cells provides a backup. It ensures that if the first queen to emerge is faulty, fails on her mating flight, or is eaten by a predator, the colony has another chance to requeen itself without further delay.

Making the Right Choice for Your Nuc

Your goal is to guide the colony through its emergency response to produce a strong, viable new queen without losing the population to a swarm.

- If your primary focus is colony survival and growth: You must intervene about a week after the nuc becomes queenless and reduce the number of queen cells to just two or three of the largest candidates.

- If you leave the colony to its own devices: You are accepting a high probability that the nuc will swarm, potentially leaving it with too few bees to survive.

Your timely intervention transforms the colony's desperate survival instinct into a controlled and successful requeening process.

Summary Table:

| Event | Timeline | Risk | Beekeeper Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Queen Loss | Day 0 | Colony becomes unstable | Confirm queen is absent |

| Emergency Queen Cells Built | Days 1-3 | Multiple cells created | Monitor cell development |

| Critical Management Window | Day 7 | High risk of swarming | Cull cells, leave 2-3 best |

| New Queen Emerges | Day 15-16 | Queen may fail or swarm | Check for successful mating |

Ensure your nucs successfully requeen and thrive. A queenless colony is a race against time. HONESTBEE supplies commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors with the reliable, high-quality tools needed for precise hive management. From durable hive tools for safe cell culling to protective gear for inspections, we support your operation's success. Contact our wholesale experts today to discuss your equipment needs and keep your colonies strong.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 5 Frame Wooden Nuc Box for Beekeeping

- Automatic Heat Preservation 6 Frame Pro Nuc Box for Honey Bee Queen Mating

- Twin Queen Styrofoam Honey Bee Nucs Mating and Breeding Box

- Portable Bee Mating Hive Boxes Mini Mating Nucs 8 Frames for Queen Rearing

- Styrofoam Mini Mating Nuc Box with Frames Feeder Styrofoam Bee Hives 3 Frame Nuc Box

People Also Ask

- How can nucs strengthen production colonies? Boost Your Apiary's Productivity & Resilience

- How should nucleus colonies be transported? Secure Your Bees for a Safe Journey

- What are the technical advantages of using specialized small-box bumble bee units? Boost Greenhouse Crop Yields Today

- What is the best time of day to install a nucleus hive? Achieve a Calm, Successful Colony Transfer

- What are the material and features of a nuc mesh transport bag? Secure and Ventilate Your Bee Colonies for Safe Moving

- What is a nucleus colony? The Essential Starter Guide for Building a Thriving Apiary in Spring

- When are queen cells ready for mating nucs? The Critical Day 11 Transfer Window

- What tools are useful when transferring frames from a nucleus hive? Ensure a Smooth and Low-Stress Move