The Beekeeper's Dilemma

Imagine a commercial apiary in late fall. The harvest is in: hundreds of barrels of rich, amber honey. But there's a problem. Much of it has crystallized into a solid, unworkable mass.

This isn't a sign of poor quality—quite the opposite. Crystallization is proof of raw, unfiltered honey. But it's also a logistical nightmare. It locks up revenue. You can't pump it, you can't filter it, and you can't bottle it.

The seemingly simple solution is to apply heat. But this is where the dilemma begins. Heating honey is not like melting butter; it's a delicate negotiation with chemistry, a high-stakes balancing act between commercial necessity and the preservation of nature's work.

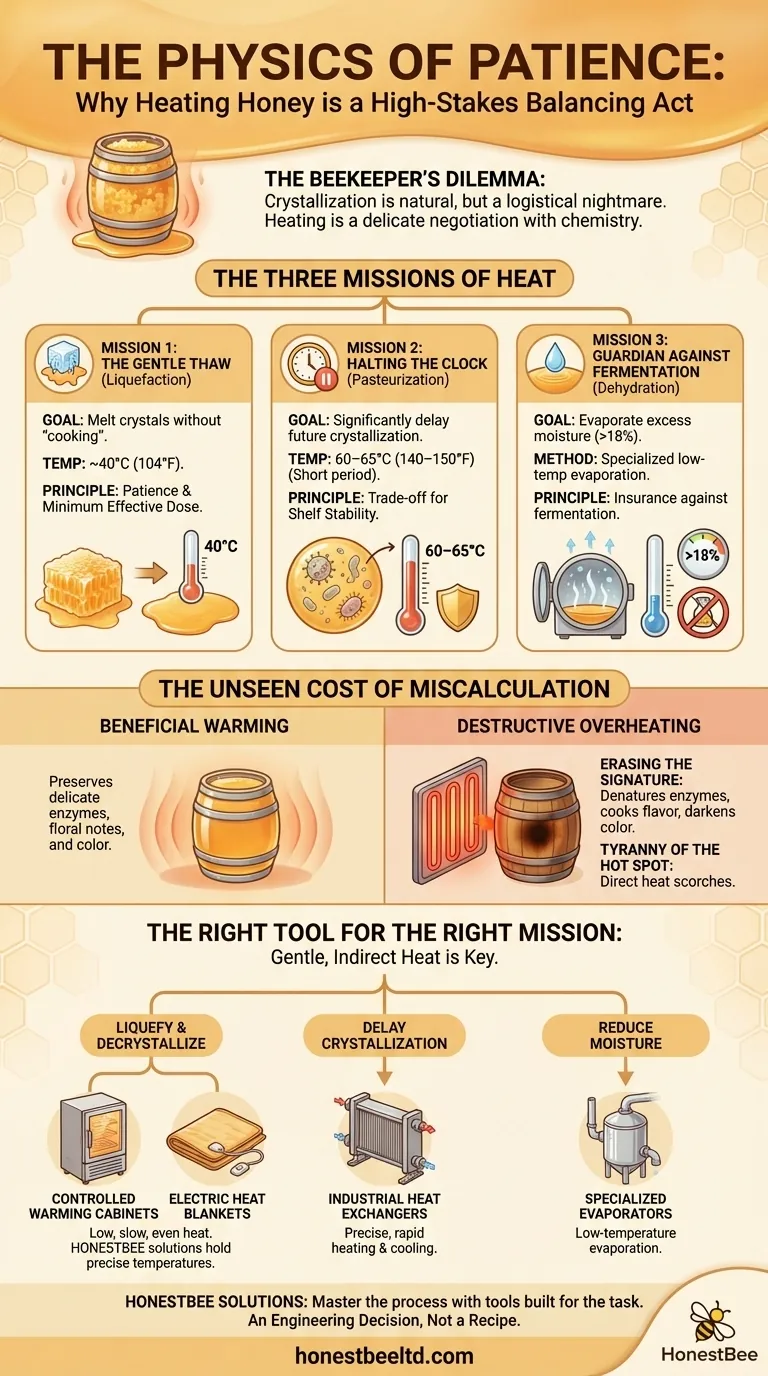

The Three Missions of Heat

Applying heat to honey is never a one-size-fits-all process. Every application is a specific mission with a unique objective. Understanding your mission is the first step toward success.

Mission 1: The Gentle Thaw (Liquefaction)

The most common mission is simply to return crystallized honey to its liquid state. The goal is to melt the glucose crystals without "cooking" the honey itself.

This requires the lowest effective temperature—typically around 40°C (104°F). It's a test of patience. The psychological temptation is to crank up the heat to speed things up. But that impatience is the enemy of quality. The principle here is minimum effective dose.

Mission 2: Halting the Clock (Pasteurization)

For a commercial product destined for a long shelf life, the mission changes. Here, the goal is to significantly delay future crystallization. This requires a more intense but highly controlled heat treatment.

Heating honey to 60–65°C (140–150°F) for a short period dissolves the microscopic sugar crystals and yeast cells that act as seeds for new crystal growth. This is a deliberate trade-off: you sacrifice some of the honey's "raw" characteristics for shelf stability. It's an economic decision, not just a technical one.

Mission 3: The Guardian Against Fermentation (Dehydration)

Honey with a moisture content over 18% is a ticking time bomb. It's at risk of fermentation, which can ruin an entire batch. The mission here is to gently evaporate excess water.

This is a specialized task, often requiring equipment that maximizes surface area within a vacuum to lower the evaporation point. It's an insurance policy written with careful thermal engineering.

The Unseen Cost of Miscalculation

The line between beneficial warming and destructive overheating is razor-thin. The consequences of crossing it are irreversible.

Erasing the Signature

Heat is the great simplifier. Excessive temperatures denature the delicate enzymes, like diastase and invertase, that signify fresh, raw honey. It can cook the subtle floral notes, leaving behind a generic, caramelized sweetness. It darkens the color.

In essence, uncontrolled heat erases the honey's unique terroir—the very signature of the flowers, the soil, and the season that makes it valuable.

The Tyranny of the Hot Spot

Direct heat is the primary villain in this story. A heating element placed directly against a drum of honey will scorch the layer it touches long before the center even begins to warm.

This is why professional honey processing is obsessed with gentle, indirect heat. The goal is uniform temperature distribution, ensuring every drop of honey is treated with the same precise care.

The Right Tool for the Right Mission

Your strategy for applying heat is only as good as the tools you use to execute it. The equipment defines your level of control.

- For small batches: A simple water bath works. It’s the definition of gentle, indirect heat.

- For commercial processing: You need tools built for consistency and scale. This is where professional equipment becomes non-negotiable.

| Your Mission | The Right Tool | The Governing Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Liquefy & Decrystallize | Controlled Warming Cabinets or Electric Heat Blankets | Low, slow, even heat. |

| Delay Crystallization | Industrial Heat Exchangers | Precise, rapid heating & cooling. |

| Reduce Moisture Content | Specialized Evaporators | Low-temperature evaporation. |

Warming cabinets and heat blankets from HONESTBEE are the workhorses for liquefaction, designed to hold large volumes at a precise, gentle temperature for hours or days. For large-scale pasteurization, tubular heat exchangers provide the surgical precision needed to hit a target temperature and cool down in seconds, preserving as much character as possible.

An Engineering Decision, Not a Recipe

Ultimately, how you heat your honey is a reflection of your business model and your commitment to quality. Are you selling a raw, artisanal product or a stable, consistent one?

Choosing the right method is an engineering decision that balances thermodynamics, chemistry, and economics. To master this process, you need tools built for the task. Contact Our Experts to find the right equipment for your scale and goals.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Silicone Rubber Honey Drum Heating Belt

- 10L Stainless Steel Electric Honey Press Machine

- Stainless Steel Manual Honey Press with Guard for Pressing Honey and Wax

- Easy Use Manual Stainless Steel Honey Press for Honey Comb

- Natural Wood Honey Dipper for Tea Coffee and Desserts

Related Articles

- How to Heat Honey Without Destroying Its Nutrients: Science-Backed Methods

- How Modern Bee Suits Combine Safety and Comfort Through Smart Design

- The Physics of a Wasp Sting: Deconstructing Bee Suit Effectiveness

- The Hidden Threat After Harvest: Why a Simple Lid Prevents Apiary Disaster

- How Beekeeping Suit Design Balances Protection, Comfort, and Durability