The Cold, Hard Physics of Survival

Winter is the ultimate filter. For a honeybee colony, survival is not a matter of endurance alone, but of architecture and energy calculus. The design of their home—the hive—dictates the odds.

Every beekeeper knows the gut-wrenching sight of a colony that didn't make it. Often, we find them with ample honey stores just inches away. The bees didn't starve from a lack of food in the hive, but from an inability to reach it.

This is not a failure of the bees. It is a failure of thermal dynamics and movement, a problem rooted in the very geometry of the hive.

The Problem with Vertical Heat

To understand the challenge, we must first understand the colony's strategy.

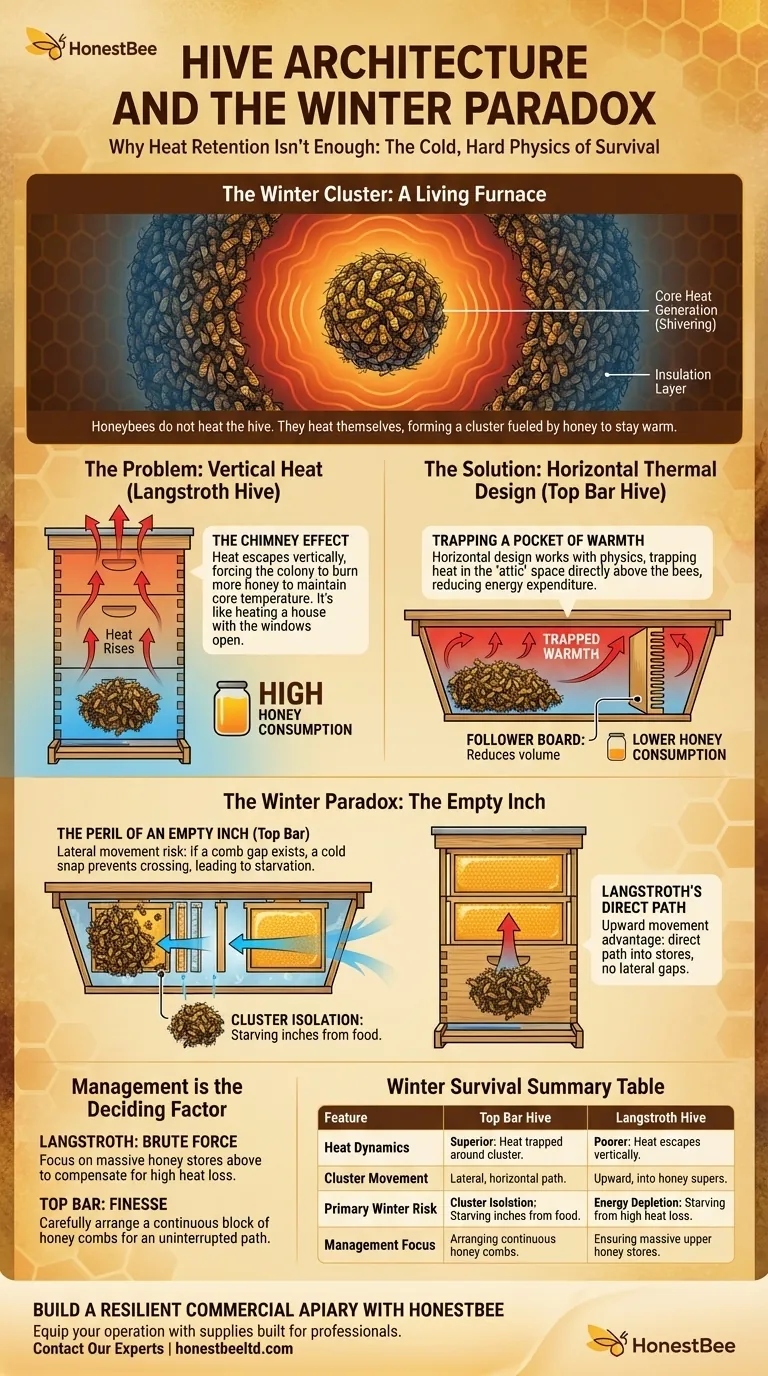

The Winter Cluster: A Living Furnace

Honeybees do not heat their hive. They heat themselves.

By forming a tight, shivering ball known as the winter cluster, they vibrate their wing muscles to generate heat at the core. The outer layer of bees acts as a living insulation, shielding the interior. This cluster is a single, slow-moving organism whose only goal is to stay warm enough to survive until spring, fueling itself with honey.

The Chimney Effect in a Langstroth Hive

In a standard vertical Langstroth hive, the colony faces a fundamental law of physics: heat rises.

The precious warmth generated by the cluster immediately ascends, escaping into the cold, empty space at the top of the hive box. This "chimney effect" forces the colony to burn significantly more honey just to maintain its core temperature. It's like trying to heat a house with all the windows open on the top floor.

An Elegant Solution: Horizontal Thermal Design

The top bar hive fundamentally alters this energy equation. Its horizontal, long-and-low design works with physics, not against it.

Trapping a Pocket of Warmth

In a top bar hive, the heat generated by the cluster rises and gets trapped in the "attic" space directly above and around the bees. There is no large vertical space for it to escape into.

This creates an insulating pocket of warm air that dramatically reduces the energy the colony must expend. The design itself becomes a tool for conservation.

The Power of the Follower Board

Top bar hives also feature a simple but powerful tool: the follower board. This is a solid panel, shaped like a comb, that allows the beekeeper to shrink the hive's internal volume.

As the colony's population naturally contracts for winter, the beekeeper can slide the follower board in, reducing the space the bees must keep warm. This is a level of environmental control that a fixed-volume box hive cannot easily offer.

The Psychological Trap of a Horizontal World

While thermally superior, the top bar hive introduces a different, more subtle risk. It's a problem not of physics, but of psychology—the psychology of a bee cluster's movement.

The Peril of an Empty Inch

The winter cluster moves as a single unit, laterally, from one comb to the next, consuming honey as it goes. The greatest danger in a top bar hive is that this path is broken.

If the cluster consumes all the honey on one comb and the next comb over is empty or contains only pollen, a sudden cold snap can make it impossible for the bees to break cluster and cross that small gap.

In this scenario, the colony starves to death, stranded, despite having pounds of honey just a few inches away. This is the winter paradox: a perfectly warm hive can still fail if the path to fuel is interrupted.

The Langstroth's Counter-Intuitive Safety

The vertical Langstroth hive, for all its thermal inefficiency, has a built-in advantage here. The cluster’s natural tendency is to move upward, directly into the honey stores the beekeeper has placed above them. The path is simple and direct. There are no lateral gaps to cross.

Management is the Deciding Factor

The hive is only a piece of equipment. The beekeeper's understanding of these dynamics is what ensures survival. Success depends on aligning your management strategy with the hive's inherent strengths and weaknesses.

- In a Langstroth hive, the management focus is on brute force: ensuring an overwhelming amount of honey is stored above the cluster to compensate for heat loss.

- In a top bar hive, the focus is on finesse: carefully arranging combs in the autumn to create a single, contiguous block of honey, ensuring the cluster has an uninterrupted path to follow all winter.

Understanding this distinction is the key to mastering the art of overwintering. It requires not just the right knowledge, but the right equipment designed for the task.

Winter Survival: A Summary

| Feature | Top Bar Hive | Langstroth Hive |

|---|---|---|

| Heat Dynamics | Superior: Heat is trapped around the cluster. | Poorer: Heat escapes vertically. |

| Cluster Movement | Lateral, along a horizontal path. | Upward, into honey supers. |

| Primary Winter Risk | Cluster Isolation: Starving inches from food. | Energy Depletion: Starving from high heat loss. |

| Management Focus | Arranging a continuous block of honey combs. | Ensuring massive honey stores in upper boxes. |

Building a resilient commercial apiary means choosing equipment that supports your management philosophy. HONESTBEE provides high-quality, durable hive components for beekeepers who understand that success lies in the details. Equip your operation with supplies built for professionals.

To discuss the needs of your apiary or distribution business, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Top Bar Beehive for Beekeeping Wholesales Kenya Top Bar Hive

- Professional Stainless Steel Pry-Bar Hive Tool

- HONESTBEE Professional Hive Top Bee Feeder Feeding Solution

- Professional Large-Format Hive Number Set for Beekeeping

- Professional Hive Top Bee Feeder for Beekeeping

Related Articles

- How to Choose Between Top Bar and Langstroth Hives for Effortless Beekeeping

- How to Prevent Cross-Combing in Foundationless Hives: A Beekeeper’s Guide

- Top Bar Hives: A Sustainable Approach to Bee-Friendly Beekeeping

- The Horizontal Trap: Hive Geometry and the Psychology of Winter Survival

- How to Inspect Top Bar Hives Without Damaging Comb: A Beekeeper’s Guide