The Architect's Dilemma

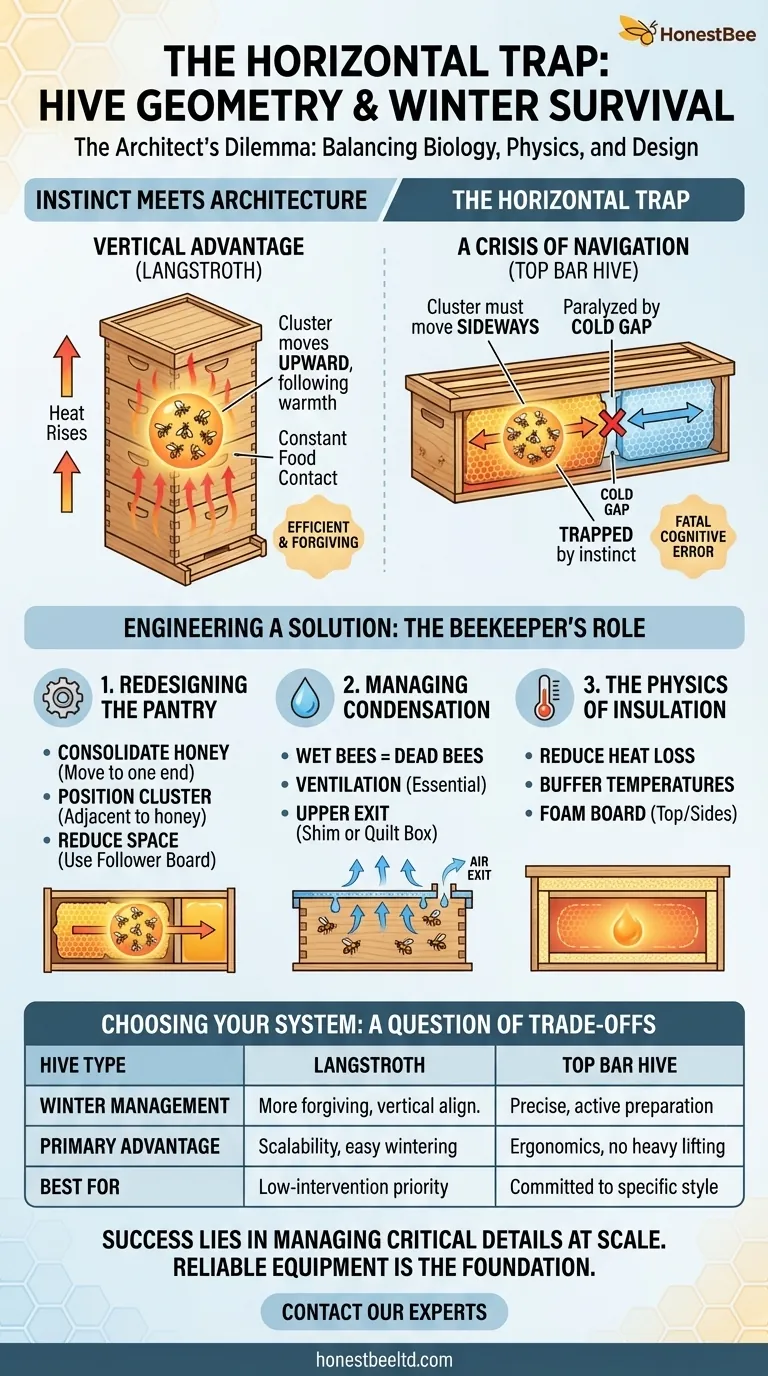

When a honey bee colony dies in winter, the amateur blames the cold. The veteran beekeeper knows the truth is often more complex, rooted in architecture and psychology.

The real killers are starvation and moisture. And in a Top Bar Hive (TBH), both are symptoms of a single, subtle design flaw—a conflict between the hive’s horizontal layout and the bee's vertical instincts.

Surviving winter isn't about fighting the cold; it's about understanding the physics of heat, moisture, and movement.

The Physics of a Winter Cluster

Honey bees don't heat their hive. That would be a colossal waste of energy.

Instead, they form a living furnace—a tight cluster of tens of thousands of bees vibrating their wing muscles to generate heat. The core of this cluster holds steady around 95°F (35°C), even when the world outside is frozen solid.

This furnace is fueled by honey. As the bees consume the honey stores in one section of comb, the entire cluster must move to the next. How they move is a matter of life and death.

Instinct Meets Architecture: The Vertical Advantage

In a standard, multi-story Langstroth hive, the system is beautifully aligned with bee biology.

Bees naturally store honey above their living space. As the winter cluster consumes its fuel, it slowly and instinctively moves upward, following the rising heat it generates.

This upward path is efficient and forgiving. The cluster remains in constant contact with its food supply, moving into warmer space. The design works with the bees' innate behavior.

The Horizontal Trap: A Crisis of Navigation

A Top Bar Hive arranges the colony horizontally. The cluster sits on a few combs, with its honey stores stretching out sideways along a series of bars.

To reach new food, the cluster must move sideways into a cold, empty section of the hive. This is where instinct fails.

A sharp cold snap can functionally paralyze the cluster. The bees are unwilling to break their warm formation to cross a gap of just a few inches to the next comb, which is full of honey. They are trapped by their own survival mechanism.

It’s a fatal cognitive error, like a person in a warm room starving because the kitchen is down a cold hallway. The colony dies, surrounded by food it couldn't bring itself to reach.

Engineering a Solution: The Beekeeper's Role

A beekeeper with a Top Bar Hive must become a systems architect, actively mitigating the risks of the horizontal design. The strategy has three parts.

1. Redesigning the Pantry

The most critical intervention is to eliminate the "cold hallway." Before winter, the beekeeper must reorganize the combs.

- Consolidate Honey: Move all honey-filled combs to one end of the hive.

- Position the Cluster: Place the bee cluster directly adjacent to the first honey comb.

- Reduce Space: Use a "follower board" to shrink the hive's interior volume, so the bees manage a smaller, more efficient space.

This creates a single, contiguous path. The bees start winter at one end of the food supply and eat their way to the other, minimizing the distance they must travel.

2. The Silent Killer: Managing Condensation

A bee colony can handle extreme cold if it's dry. But the bees' own respiration creates warm, moist air. When this air hits the cold inner surface of the hive lid, it condenses and drips back down.

Wet bees are dead bees.

Ventilation is not optional; it's essential. A small shim, the size of a popsicle stick, placed under one edge of the lid creates a tiny upper exit. This allows moist air to escape without creating a chilling draft. Some beekeepers use quilt boxes filled with wood shavings to absorb moisture, acting as a natural dehumidifier.

3. The Physics of Insulation

The goal of insulation is not to heat the hive, but to reduce heat loss and buffer the colony from sudden temperature swings.

Placing rigid foam board insulation on top of the lid and against the sides helps the cluster conserve the energy it generates. This makes them more resilient and better able to navigate their horizontal world.

Choosing Your System: A Question of Trade-offs

The Top Bar Hive's primary advantage is ergonomic. Managing individual bars avoids the back-breaking work of lifting 50-pound honey supers. But this benefit comes with a lower margin for error.

| Hive Type | Winter Management | Primary Advantage | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langstroth | More forgiving; aligns with vertical instinct. | Scalability and ease of wintering. | Beekeepers prioritizing a low-intervention, forgiving system. |

| Top Bar Hive | Demands precise, active preparation. | Ergonomics; no heavy lifting. | Beekeepers committed to its specific management style. |

Success in beekeeping comes from understanding that a hive is more than a box. It's an environment that can either support or conflict with the powerful instincts that have guided bees for millions of years.

At HONESTBEE, we understand that professional beekeeping is a game of managing these critical details at scale. We supply commercial apiaries and distributors with the durable, wholesale-focused equipment needed to manage operational risks across any hive system. Whether you're preparing for winter or expanding your operation, having reliable equipment is the foundation of success.

To ensure your apiaries are prepared for the challenges of any season, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Long Langstroth Style Horizontal Top Bar Hive for Wholesale

- Langstroth Bee Hives Bee Keeping Box for Beginners Beekeeping

- Wholesales Dadant Size Wooden Bee Hives for Beekeeping

- Professional Galvanized Hive Strap with Secure Locking Buckle for Beekeeping

- Professional Dual-End Stainless Steel Hive Tool for Beekeeping

Related Articles

- How Beekeepers Can Stop Ants Naturally Without Harming Their Hives

- How to Prevent Cross-Combing in Foundationless Hives: A Beekeeper’s Guide

- Essential Beekeeping Equipment for Beginners: Functions, Selection, and Best Practices

- Essential Beekeeping Tools: How Strategic Preparation Boosts Hive Health, Safety, and Honey Yields

- The Art of Intervention: A Systems Approach to Beehive Maintenance