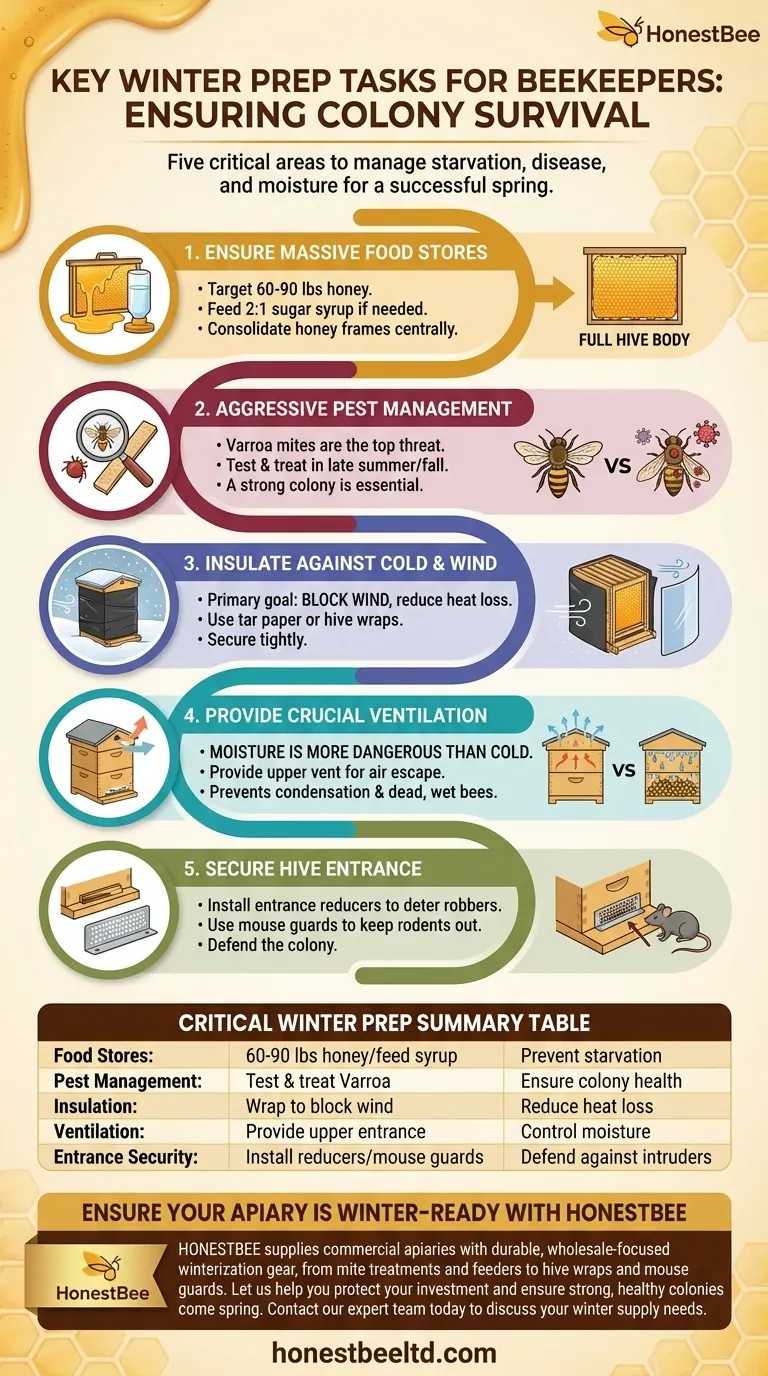

To successfully prepare a beehive for winter, a beekeeper must focus on five critical areas: ensuring massive food stores, aggressively managing pests like Varroa mites, insulating the hive against wind and temperature drops, providing crucial ventilation to control moisture, and securing the hive entrance against intruders. These actions collectively address the primary causes of winter colony loss—starvation, disease, and moisture.

The goal of winter preparation is not just to keep the bees warm, but to create a stable, dry, and food-rich environment. A successful strategy manages the interconnected threats of starvation, moisture, and pests, ensuring the colony has the resources to survive until spring.

The Foundation: A Strong and Healthy Colony

Before any winter-specific tasks begin, the health of the colony during the late summer and fall is paramount. A strong, populous, and healthy hive is the single most important factor for winter survival.

Why a Strong Population Matters

A large population of bees is required to form a "winter cluster." This is a tight ball of bees that vibrates to generate heat, keeping the queen and the center of the cluster at a survivable temperature, even when it is freezing outside. A small colony simply lacks the numbers to generate enough heat.

Controlling the Varroa Mite Threat

Varroa mites are the most significant pest affecting honey bees. Mites weaken bees by feeding on their fat bodies and transmitting viruses. A colony entering winter with a high mite load is severely compromised and unlikely to survive, making late summer and fall Varroa testing and treatment an essential, non-negotiable task.

Ensuring Adequate Food Stores

Starvation is a leading, and entirely preventable, cause of winter colony death. Bees do not hibernate; they are active within the hive all winter and consume significant amounts of honey to fuel their cluster and generate heat.

How Much Honey is Enough?

A full-sized hive in a cold climate may need 60-90 pounds of honey to survive the winter. Your goal should be to leave them with a full hive body of honey after the final harvest.

When and How to Feed Sugar Syrup

If the colony's natural stores are insufficient, you must feed them. This is typically done in the fall after any honey for human consumption has been removed. Feed a 2:1 sugar-to-water syrup (by weight), as the thick consistency is easier for bees to process and store.

Consolidating Honey Frames

Bees can become "marooned" on empty frames and freeze, even if honey is just a few frames away. Before closing the hive for winter, consolidate all the honey frames together in the center of the upper hive body. This ensures the winter cluster can easily move from one frame to the next without breaking apart in the cold.

Managing the Hive Environment: Insulation and Ventilation

The physical hive must be prepared to buffer the bees from the worst of the winter weather. This involves a careful balance between insulation and ventilation.

The Goal of Insulation: Blocking Wind

The primary purpose of winter insulation is not to "heat" the hive, but to block wind and reduce the rate of heat loss. A windbreak is often more valuable than thick insulation. Methods like wrapping the hive in black tar paper or using specialized hive wraps are common.

Practical Insulation Methods

Wrapping the hive body in black plastic or tar paper helps absorb solar radiation on sunny days and provides an excellent windbreak. Ensure the material is secured tightly to prevent it from flapping in the wind.

The Critical Role of Ventilation

Moisture is more dangerous than cold. As the bees consume honey and respire, they release a large amount of water vapor. If this moist air hits a cold inner surface, it will condense and drip back down onto the bees. Wet bees are dead bees. To prevent this, you must provide a small upper entrance or vent for this moist air to escape.

Securing the Hive Entrance

The final step is to secure the hive against invaders seeking warmth and food.

Installing Entrance Reducers

An entrance reducer constricts the main hive opening to its smallest setting. This makes it easier for the guard bees to defend against robbing bees from other hives and prevents drafts.

Why You Need a Mouse Guard

Mice frequently try to move into the warmth of a beehive for the winter. They will chew comb, eat honey, and disturb the cluster, often leading to the colony's death. A simple metal or hardware cloth mouse guard installed over the reduced entrance will keep them out.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Effective wintering requires balancing competing needs. Misunderstanding these trade-offs can be as harmful as doing nothing at all.

Over-Insulation and Condensation

Sealing a hive too tightly in the name of warmth is a common and fatal mistake. Without adequate ventilation for moist air to escape, you create a cold, damp environment that is far more deadly than a cold, dry one.

The Risk of Late Feeding

Feeding syrup too late into the fall can stimulate the queen to lay eggs when the colony should be reducing its brood. This can disrupt the formation of the winter cluster and adds excess moisture to the hive at the worst possible time.

Ventilation vs. Heat Loss

Creating an upper entrance for ventilation will inevitably allow some heat to escape. This is a necessary trade-off. Losing some heat is far preferable to allowing condensation to build up and rain down on the winter cluster.

A Final Checklist for Winter Success

Your specific actions should be guided by your climate and the state of your colony.

- If your primary focus is a new or weaker colony: Prioritize consolidating all honey stores directly above the cluster and ensuring they have more than enough food to last the winter.

- If you live in a very cold or windy climate: Focus on providing a solid windbreak and wrapping the hive, while ensuring you still have a small upper entrance for moisture ventilation.

- If your colony is strong but had pest issues: Confirm that your Varroa mite counts are near zero before closing the hive for winter, as this is their last chance for survival.

By addressing food, pests, moisture, and security, you give your bees the best possible chance to emerge strong and healthy in the spring.

Summary Table:

| Critical Winter Prep Task | Key Action | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Food Stores | Ensure 60-90 lbs of honey; feed 2:1 sugar syrup if needed. | Prevent starvation. |

| Pest Management | Test and treat for Varroa mites in late summer/fall. | Ensure colony health. |

| Insulation | Wrap hive to block wind (e.g., tar paper). | Reduce heat loss. |

| Ventilation | Provide a small upper entrance. | Control moisture (condensation kills). |

| Entrance Security | Install entrance reducer and mouse guard. | Defend against robbers and mice. |

Ensure Your Apiary is Winter-Ready with HONESTBEE

Preparing your hives for winter is complex, but having the right supplies makes it straightforward. HONESTBEE supplies commercial apiaries and beekeeping equipment distributors with the durable, wholesale-focused gear needed for successful winterization—from mite treatments and feeders to hive wraps and mouse guards.

Let us help you protect your investment and ensure strong, healthy colonies come spring. Contact our expert team today to discuss your winter supply needs and secure your apiary's success.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- HONESTBEE Classic Pry Bar Hive Tool with High Visibility Finish for Beekeeping

- Professional Grade Foldable Beehive Handles

- Premium Comfort Grip Spring-Loaded Hive Handles

- Professional Drop-Style Hive Handles for Beekeeping

- Yellow Plastic Bucket Pail Perch for Beekeeping

People Also Ask

- What are the uses of a hive tool in beekeeping? The Essential Multi-Purpose Key for Your Apiary

- What are the common types of hive tools? Discover the Best Designs for Efficient Apiary Management

- What are the alternatives to a hive tool? The Essential Tool for Every Beekeeper

- What are the different end shapes found on hive tools? Master Beekeeping with the Right Gear

- What factors should be considered when choosing a hive tool? Select the Right Tool for Your Apiary